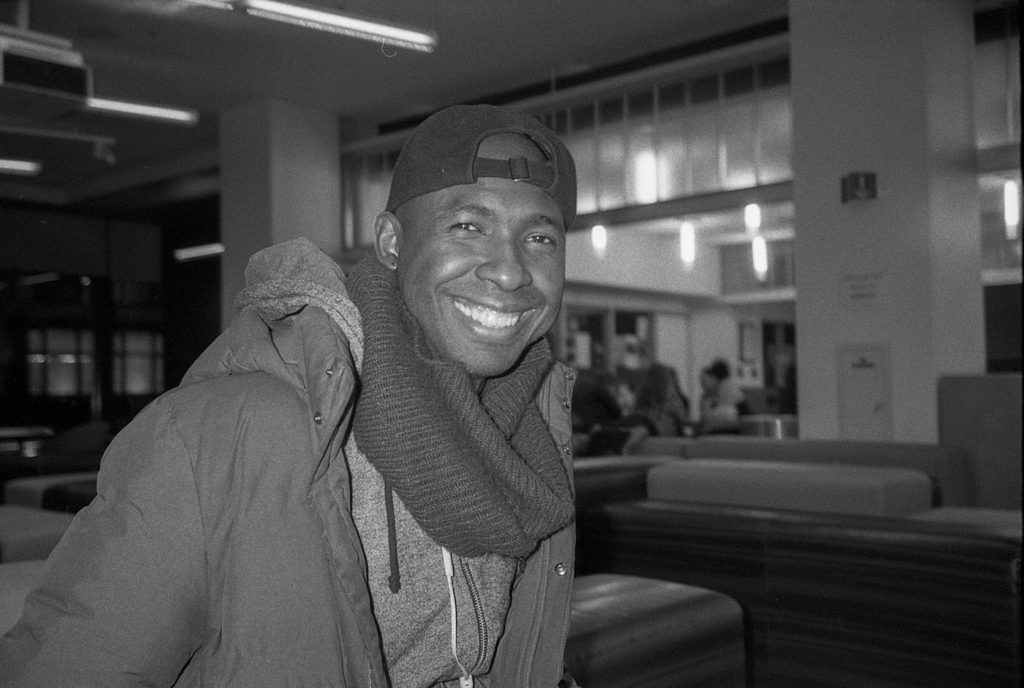

A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Leasho Johnson

Marsha Pearce: Hello Leasho. How have you been handling the unfolding events of the pandemic and global protests against racial injustice?

Leasho Johnson: Hi Dr. Pearce, thank you for inviting me to take part in this series. It is a great initiative to contribute to, especially during this time. I would say I feel overwhelmed, caught in a state of questioning or confrontation; a sense of not standing on level ground. I want to say the particularities of how Black people are treated and situated in this world will always be confrontational – either directly or indirectly. It breeds unease, frustration, and anxiety with almost everything we do. There is a feeling of over-stimulation; that heightened awareness in conjunction with race that never leaves my mind. The anxiety of coming to America, to a majority white institution, and where I am left at the end of an MFA course of study – in the heights of a global pandemic – surely do not put me at ease.

It’s comforting, however, that now in this time, globally, we share the same kind of uncertainty due to the atmosphere this pandemic ‘transmits.’ Not knowing what’s next; the fear of intimacy becoming deadly, or the anxiety/danger that comes from being in public spaces, or that sense of isolation and the sheer swiftness of the future (time) are all things we are forced to reflect on. I would say the worst part about COVID-19 is that it is indiscriminate and the best part about it is that it is indiscriminate. It has surely bound us together, despite everything that society has used to separate us. It has exposed a lot of our vulnerabilities institutionally, psychologically, environmentally, and systemically. There is no point of being passive, we have no choice but to deal with them. Despite all that, I have been holding myself together the best way that I can; the only way that I can— creating work. Leading up to the closing of the school, I have been working diligently in my living room, reading, applying for opportunities, streaming films, binge-watching online (now the common side effect of this pandemic), running at night, and staying in contact with my family and friends back home, in Jamaica.

In past work, you have used dancehall culture to disrupt and resist colonial images and ideologies. The black body has played a critical role in your subversive efforts. How are you thinking about the black body and resistance in your new portrait paintings, which seem to involve the shaping forces of mythology and hybridity? Is Dancehall culture a sustained reference point in these new works?

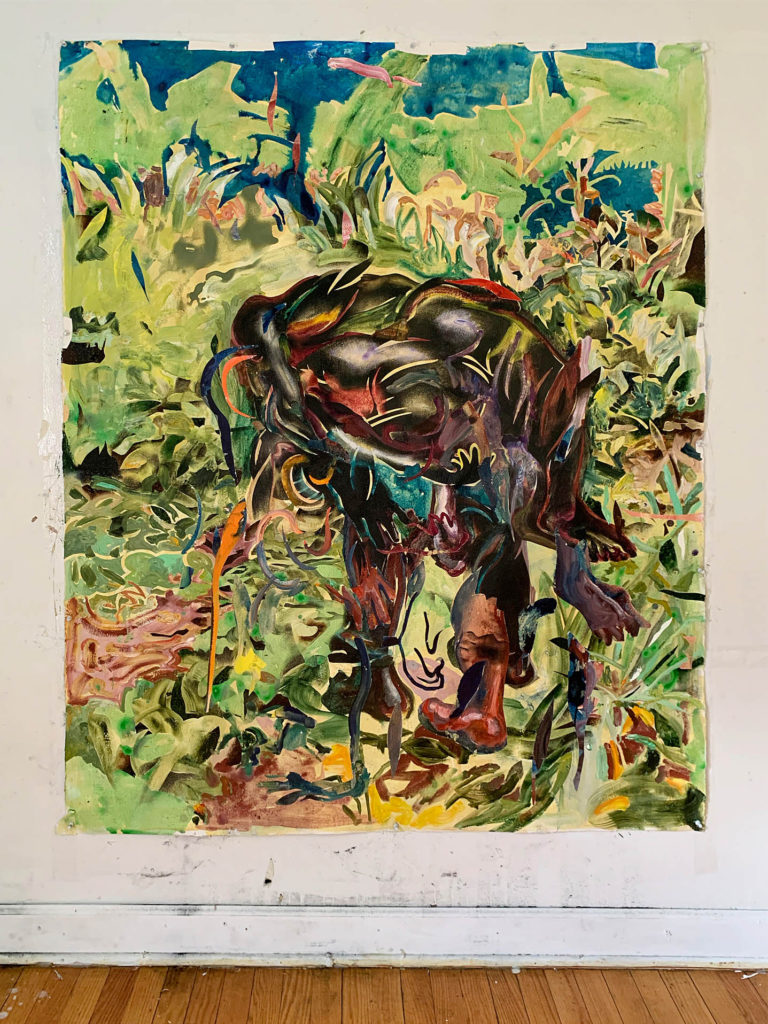

In an effort to see the larger meaning of dancehall and its role in forming identity, it was impossible for my past works to escape their didactics and so I needed to find further ways of deepening my approach. The works always do include, if not exclusively, the Black body but I always find the avoidance of my most critical subject: my own Black, queer body, and its place in the larger world problematic. I am Black, male, and queer but I never thought I could talk about the complexities openly and clearly without dealing first-hand with home, and its afflictions with Western ideas of blackness or Black bodies. Its role in its inception as a machine that is built on the subjugation of black bodies becomes perpetuated with our colonial legacies around otherness. I want to discard the level of shame that comes from bible quotations, as if not in the same breath, reducing my blackness to subhuman, unclean, and valueless.

The ‘portrait’ paintings, however, as much as they are about a Black subject, are not about direct representation. I want to think that these paintings describe more a condition or a presence than an actual likeness. Artists like Kehinde Wiley and Toyin Ojih Odutola and many more, deal with that form of representation in the Western canon. Their power and purpose come from the occupation of Black figures in spaces where white figures normally occupy. The presentation of their subjects are fixed and rendered in their likeness. What is still left unexplored though, is what happens beneath the surface of their subjects. Can they only find purpose in occupying the same spaces as their white counterparts? Can you represent Black bodies without galvanizing Western platforms of beauty? Do I need to justify my humanity by following in the same modes of value as white artists before me? That for me is the function of portraiture— the surface, the search for likeness, and with that, I think, my ‘portraits’ escape that definition.

My current interest in my artwork still ignores Dancehall’s obvious attributes such as fashion and acoustics. Its forms, rules, methodologies, and its participants shift over time. It is passed on as generations reinvent and repurpose its role in culture and its forms of expression align with the current. Its modes of representation are fugitive forms like sound waves and choreography, that are intangible if not transparent like folk tales. The movement of Dancehall itself remains fugitive, you can only choose to be a part of it at points in time or reject it, and so I had to formulate my thoughts to respect that.

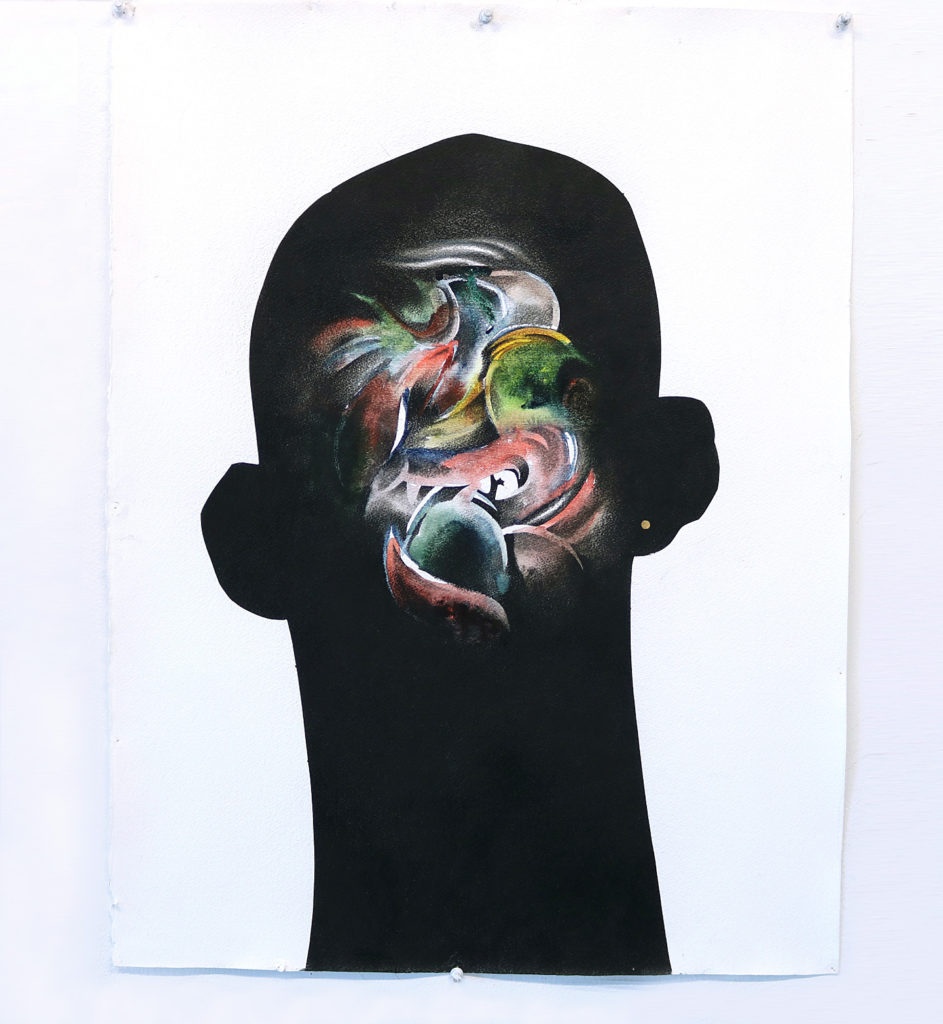

Many say this pandemic – with self-distancing and self-quarantine – is a time for introspection. As you have stated, your new portraits go beyond the surface of the flesh to explore and witness an interior space. What can you tell me about the place of interiority and reflection in these works? I am particularly interested in hearing about the works you have titled “self-portraits.”

I think introspection is a good thing. It is required for healing and understanding. I want to think that is the main premise in my artistic pursuit. Making art in a studio requires a lot of introspection and questioning. When I started the self-portrait pieces I was thinking a lot about what is painting and what is drawing? And if they are two separate actions that use the same tool (the body), how can I blur those boundaries? I was also thinking a lot about myself as a subject but less about the production of portraiture in its traditional sense. I am intrigued by art that comes from the subconscious. What is revealed through the medium, and what is projected through the mind? How much of that is wrapped up in perception, from stereotypes and media? How much of that is influenced by memory and history? If music and words are mediums that express interiorities? What role do colour and form play? I realised that my interest aligned with Abstract Expressionism. Long story short, abstraction connected painting to evocations of emotions, after decades of paint (the material) being liberated from representation (the academy). Then the Abstract Expressionists in the 1940s connected abstract painting to the artists’ body. Personally, I prefer the works of Francis Bacon and Willem de Kooning simply because of the association to their own bodies. Their work is connected to notions of gender, sexuality, and desire; more so Bacon because of his interest in evoking emotion through the visceral effects of the macabre. I realised, while thinking about these things, how can I reflect my own feelings in my characters? My works really want to occupy that strange psychological space that is recognizable and unrecognizable. At the same time, referencing symbolism, stereotyping, code-switching, choreography, and gender dynamics, all of which are critical to my Black experience— crucial but almost impossible to undertake. This I felt could be unified by connecting with materials and making.

My current approach to painting comes from thinking about colour and material and their connection to colonialism, anthropology, and how that’s all connected to aspects of Blackness. The creation of the Other and the mythologies of monsters are created by Western concepts to justify their own inhumane actions of removal and othering.1 James Baldwin talks about this in his essay, Unnameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes. With that, I think of Blackness also as a mythology. The process of adding and removing is something I now employ in my paintings, either as a metaphor for the creation of these ‘others’ or as a way of preventing the entrance of the viewer. In other words, I want my Black bodies to inhabit a metaphysical space that frees them from definition.

I want to stay in this vein of self-reflection. How has graduate study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago impacted your creative process?

Education is a hell of a thing for sure. I am grateful for meeting and working with so many great minds. Mike Cloud, Riva Lehrer, Danny Giles, Candida Alvarez, Richard Hull, Judith Geichman, Ayanah Moor – I would like to extend my thanks to them. And a special thanks to Richard Deutch and Michelle Grabner. I have truly enjoyed assisting their teaching. And of course, Arnold Kemp, with whom I had a very challenging and meaningful semester of studio advising.

I have grown considerably. The experience opened up a lot about art making and how I see myself moving forward. Throughout my entire time there, I came to acknowledge what I know, but at the same time realise how much I didn’t know. Having colleagues that can help inform, challenge, and point you in the right direction is important in realising yourself as an artist. Besides reminding me of my first love – painting – I had to relearn my approach and understanding of material and colour. Michael Taussig’s book What Color is the Sacred? was a fantastic contribution to this new understanding. It describes colour not just as elements that refract light but as a substance that is alchemical and spiritual in its effects. Taussig talks about the effect color has on the body as something that has taste, smell and magic. The book explains the relationship colour had within Black and Brown societies before colonialism. Instantly my mind went to sugar manufacturing in the Caribbean – the extraction of colours and spice – and how those “polymorphous magical substances”2 are sourced through Black and Brown bodies to construct modern Western civilisations. A huge eye-opener of course, and after that, I never saw colour the same again. I wanted to work with the purest materials, in their rawest forms – before they are named, packaged and sold. Now I make my own paints to work with.

You mentioned representation earlier and I want to return to that, especially since your work attends to questions about identity. I recall Stuart Hall’s (1991) observation that: “questions of identity are always questions about representation…and they almost always involve the silencing of something in order to allow something else to speak.” What more can you share about representation in your work? How do ideas about silences and voice feature in your practice? Do any of these concerns feel considerably urgent in our present context?

If I am silencing a voice, that would probably be that voice in my head called ‘doubt.’ I have witnessed in my journey as a Black artist, how little of us have made space for ourselves just to believe in ourselves. My work is definitely questioning identity. I want to acknowledge the past but embody the present. If nothing else, I want to accept and move beyond preconceived boundaries. If I am silencing the colonial, racist propaganda that has persisted in narratives of Black lives so that I can move freely within myself, and out into the larger world, then it is urgent.

One of the themes that I decided to explore in my work is Afro-Caribbean folklore – maybe an imagined version using dancehall as the site – mainly because of folklore’s proximity to authentic African understanding. I thought of the principle of the white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland and the black spider of Anansi folktales, metaphorically speaking, and I imagined having to choose to follow one of them. I did this while I was at grad school as a meditation – thinking which path I should take moving forward in my practice, to pursue truth. I had to do this because with the knowledge I was acquiring, I had to decide whether to reinforce the preconceived notions of self (or the lack thereof) as a minority; ignoring my inherited self. Was I learning about art? Yes, that is what I came here for. But who was I learning this from? How do I learn to listen to my own voice? Race was not an acknowledged part of that. The act of silencing is to actively turn inwards. Anansi was that path back home, psychologically speaking.

Black representation as an initiative, is constant and active. It is more than just for the sake of ‘diversity’– an add-on to break up Western monotony. It is continuously pursuing to see ourselves as complex, as deep, as worthy – as human beings. I want to claim my humanity in its fullest form, not just through the fragments of lost history, but though reimagining self, in the now. I related to Toni Morrison when she said:

“My whole education was to make sure I didn’t believe things like that. I dismissed all sorts of things that were indigenous in my family – superstition and discredited information; the discredited way of knowing that discredited people always have. But when I began to write, that was the place where I had to go. That’s where the information was; that’s where the images were; that’s where the language, the colour came, in these tales, folk tales…”3

— Toni Morrison 1988

I took note of that because I think of all the misrepresentation and silencing that happens in my immediate culture, like Vodoun and Obeah; how we fear it; fear each other, and the discontinuation of folk culture, like verbal storytelling. I think the demonization of our culture through the media, by colonial efforts, forces us away from our ancestral path of understanding ourselves, which means representation is key. I will never take for granted Black imagination. Black imagination is very important for the realisation of Black identity.

References

- James Baldwin, “Unnameable Objects, Unspeakable Crimes (The white problem in America”, Ebony magazine special edition, August 1965. Republished, New York: Lancer Books, 1966. p.9.

- Michael Taussig, What Color is the Sacred? The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London, 2009.

- Toni Morrison interview | American Author | Award winning | Mavis on Four | 1988

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UAqB1SgVaC4&t=697s

Stay connected with Leasho Johnson:

Instagram: @leasho_johnson

Website: leashojohnson.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.