A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Simon Tatum

Marsha Pearce: Hello Simon, it is a pleasure to connect with you. How are you? How are things in Ohio? Are you keeping in touch with happenings in the Cayman Islands?

Simon Tatum: Hello Dr. Pearce! Yes, it is a pleasure to connect with you as well. I really appreciate your taking the time to produce this conversation series. I’ve enjoyed reading it, seeing new artworks and hearing thoughts from Caribbean artists and creatives who I respect very much. It has been nice to have your Quarantine and Art series as an information hub. I have visited your conversation webpage often this summer, while working from my apartment in Kent, Ohio.

Things in Ohio are okay. The virus cases are still rising in this area of the US. There have been additional rules put in place, forcing people to wear masks when entering public spaces. There are also many conversations happening this month at my university, in preparation for classes to resume in the fall. It will be a learning curve for everyone; trying various versions of hybrid classes or remote learning. There is a lot going on, really. I find all the news, information and conversation difficult to navigate sometimes. All the information and negative energy generated by it can quickly become compounded, especially when I am also worrying about the circumstances of my family, girlfriend, friends, and colleagues living elsewhere in the world. So, this summer I am trying a new approach. I am trying to remain present when possible. I am taking things a day at a time and enjoying the little moments – like the nice interactions with people in Kent, making sure that I enjoy every minute of my video calls with loved ones living abroad, feeling the summer weather and starting my mornings with coffee on the porch, watching a new movie every night before settling for bed. Those small things have brought about a peace of mind.

I am keeping up with things happening in the Cayman Islands. My home country has done well with their efforts to keep their citizens safe and control the spread of the virus within the three islands. This has been accomplished by mass testing, strict social distance rules and postponing travel for tourists wishing to enter the islands. I am comforted by the knowledge that my family and friends, who remain in Cayman, can be safe.

You’re an MFA candidate for the Sculpture and Expanded Media programme at Kent State University. What can you tell me about your recent experiments with three dimensional forms? And how is the programme impacting your practice?

Yes, I am an MFA candidate. In September, I start the third semester of a four-semester MFA programme. The first semester at the Kent MFA programme was a return to the three-dimensional form. I learned the process of object casting with silicone moulds. Learning that method helped me experiment with three-dimensional forms by working in multiples. I used the casting process to help me combine hand-sculpted figures with other aesthetics captured from found objects. The casting process also helped me think about the relationship between form and surface by having multiple copies of the same form with which I could try various surface treatments. A good example of these object castings would be my Souvenirs.

The second semester of the programme, before it was interrupted by COVID-19, was focused on installation. I was thinking about creating various elements, like three- dimensional forms, hand-drawn images, found objects, and video to make a single project that told a story about traveling to an island resort. This installation was postponed when the virus restrictions were put in place. The remaining time in the semester was focused on digital media and thinking about how projects could be presented online. How could a work exist online while also existing as a physical object or a graphic in a public space? I wanted to find a way to have a project that could have a single subject and different formats to allow it to exist online and within a public space. By the month of May, I designed an installation that I currently call my Departure Project. It is a project that evolved from a text – a journal entry I made about a travel experience. That text was turned into the text format of an inner monologue that illustrates what’s happening within the head of a traveler as they are on their way to an airport and preparing to board a plane. That text can be accompanied by a video loop or a storyboard of 30 images that can be shown online through my website or YouTube channel. Both the video and story board are still in progress. The sculpture in public space will be a scroll poster board that can be set in a hallway and it contains a graphic and summary text that are associated with the monologue video. The poster will also have a QR code placed on it that can be scanned by a smart phone and direct the viewer to the digital portion of the project.

The third semester of the programme will be focused on generating research. I will need to take the subjects and project formats I enjoy and use them as a compass to connect with other peer reviewed resources and begin planning my thesis research paper.

The programme and the Kent School of Art have affected my practice in two ways. The first way is that the professors here have really helped me with formal analysis. They have often critiqued my work based on the basic elements of design, composition, perspective, form (and time with relationship to video). This style of criticism has been helpful. It has reminded me that even though my topics and references might be interesting and potent, the formal elements of visual art, which can be read from the work, can enhance the presence of those topics and references for the viewer. For example, when making the Souvenir works, I would be given all sorts of suggestions about changing scale, changing colour, changing material, changing surface treatments. Really, with all the suggestions, I could have easily turned one of the souvenir artworks into 30 or 40 other works. It made me realise that formalists will try every variation of an artwork until the topic is exhausted. I have a hard time working this way, but I am learning how it can help an artist find an optimal artwork type to carry a message. On the other hand, I suppose the danger of working this way is that an artist could be making, essentially, the same type of work for years with minute changes, causing the work to become unsatisfying or predictable if the artist is not careful.

The second way the programme has affected me is through the presence of the faculty. It is inspiring to be surrounded by a team of faculty artists and art historians who are mostly young and active in their fields. Watching them pursue their careers alongside their family lives is a refreshing reminder that a career can be built around the home life you want, rather than something separate from it.

You mentioned your Souvenirs. I would like to hear more about these works. I saw an intriguing image of one of the pieces – it appears to be a miniature fallen monument.

In the first semester, I spoke to my tutors and I decided to concentrate on tourism as my central topic. These works were inspired by the souvenir figurines I collected from thrift stores in Ohio towns and thrift stores in Barcelona (I get to visit Barcelona occasionally to see my girlfriend who lives there now). The figurines were things I imagined I would see in a tourist shop in Grand Cayman – things like British soldiers, pirates, sailors (or maritime characters), Black figures playing drums, women feeding birds. I found it funny how such figurines have become universal for representing tropical areas because of colonial folklore and legacy. So, I made cast molds of the figurines I collected, turned them into plaster and put them on top of other plaster casts I made from glass objects like ashtrays, dishes, or, my favourite, a glass pineapple light bulb. The figures placed on the casts of the glass light bulb do feel like fallen monuments, and I enjoyed the suspense of the figures floating in the air like they could fall over with time. Originally, they reminded me of some Catholic saint statues that were pushed over and re-appropriated within cemeteries in Havana, Cuba. I saw these things while visiting friends in Havana and viewing the 2019 Havana Biennial. However, with recent events re-energising Black Lives Matter movements during the pandemic, I feel that these little souvenirs will inherit new meaning when evaluated within contemporary discussions about controversial monuments and their place in communities. I like the position that can be approached by this work and I look forward to developing them further as I begin working on my thesis paper and exhibition.

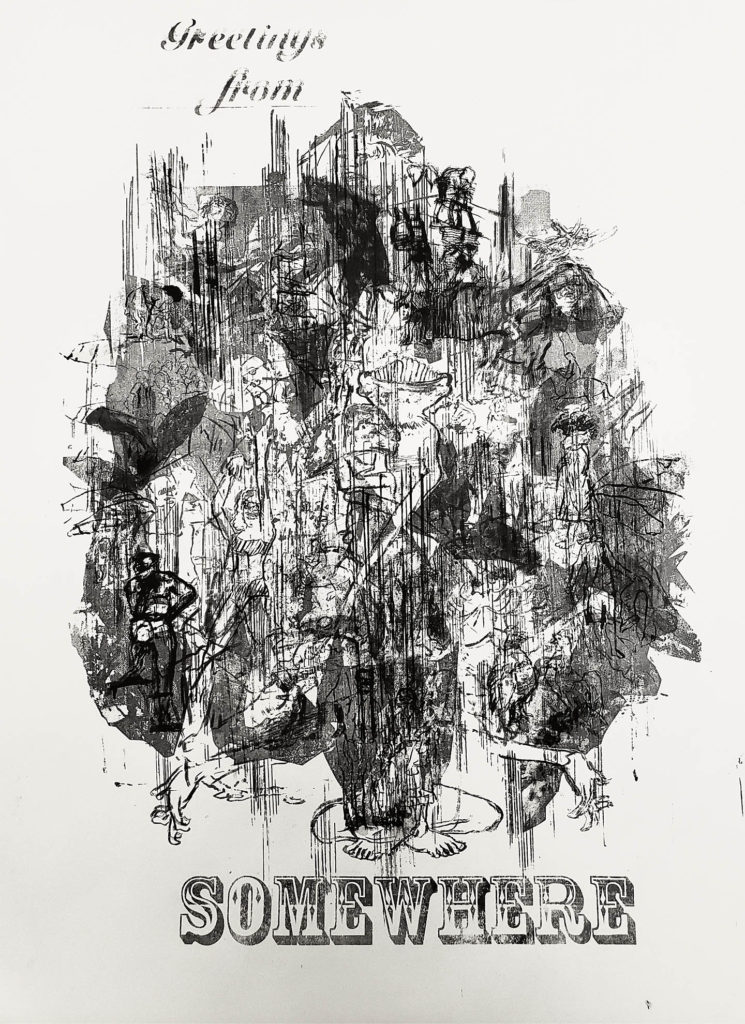

You’ve also been working on new graphite images on paper. I am drawn to your piece titled Greetings from Somewhere. It is an amalgam of visual references held in dialogue by rich, compelling mark making. Please tell me about this work.

Yes, I continue making works on paper, even if I am trying to sort out other projects or works that use mixed media and different skill sets. I am working on a new series of drawings titled Still Life 2020. Drawing keeps me present and helps me work through ideas and process information. That obsession with drawing was taught to me by a friend and previous studio mentor, Matt Ballou, and it has been compounded over the years with ideas about image registration and image design that were taught to me by another studio mentor, Chris Daniggelis.

My technique for creating the work Greetings from Somewhere involves taking graphite powder and mixing it with some sort of water-based or acrylic binder to make a graphite silkscreen. I now have various graphite paste formulas. I use them to create images on paper that are copied from either photograph halftones or hand-drawn graphics on transparencies.

Originally, I used the graphite screen-printing to create images that showed unidentified black people captured within various photograph portfolios stored in the Cayman National Archive. I would place those reprinted faces in conjunction with places or locations in the Cayman Islands. At that time, I was trying to use that method as a way to be in conversation with the archive and show how certain perspectives can be left out of the historical narrative causing displacement of Black history within the islands. These print works were shown in various exhibitions including the Carifesta XIII showcase in Barbados in 2018, where they were referenced by Rob Perrée during his review for Africanah.org.

In winter 2019, I used the graphite screen-printing technique to create images that could work as a poster for a Caribbean retreat. The idea was prompted by a friend’s coffee mug that had the caption “greetings from somewhere” and showed a graphic of palm trees on a deserted beach. I wanted to follow that logic and use the same text caption alongside a new image that showed a busy amalgam of images referencing tropical creatures, animals, flora, tourists, pirates, mermaids, domestic helpers, indentured servants, a plantation worker, a maritime character, a working-class family and a colonial magistrate. All these characters visually combined by skewed perspective and vertical lines that hint at the aesthetic of static or rainfall. Together the elements make an image that is a bosquet of figures with Caribbean references, or a bosquet of confusion. For me, the image serves as a reminder of all the things that are either strategically put in tourist advertisements for the Caribbean or strategically left out. And in reflection, I believe that the Caribbean is actually a place that combines all these things at once.

Your body of work titled Tropical Forms has taken different shapes over the years, since its early focus on Cuban contract workers in Germany. Yet, a constant thread has been the idea of migration. In what ways has this work evolved?

The tropical forms have been such interesting projects. Like you mentioned, Tropical Forms originated in response to a narrative about Cuban contract workers living in Germany. While on residency in Leipzig in 2017, I was looking for a subject to focus on while creating new paintings. During my second day at the residency site, an old spindle factory, I was shown the archive booklets of the spindle factory and saw various groups of Black and Brown men working within the factory during the GDR years when East Germany was still part of the Soviet Union. It turned out that some of the men were Cubans, traded by Castro’s government as short-term contract workers in exchange for German machines, such as automobiles and washing machines. The original tropical forms were made at the spindle factory as a commemoration of these Cuban workers within the factory space.

The concept for the tropical forms evolved as the project was invited to different sites. For the Arrivants exhibition curated by Veerle Poupeye and Allison Thompson in 2018 at the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, the tropical form became an installation within a hall of paintings. The installation lost its portrait references to specific Cuban workers, and instead became a figural work celebrating the creation of hybrid forms or mixed-race people through sexual encounters. In 2019 at the Tropical Visions exhibition curated by Natalie Urquhart and William Helfrecht at the National Gallery of the Cayman Islands, the tropical forms regained their Cuban portraits and became forms that referenced potted plants or trees. Various stems of these plants reached through the back hall of the exhibition space finding their way to air ventilation systems, as if the tropical forms were trying to find a way out of the gallery space.

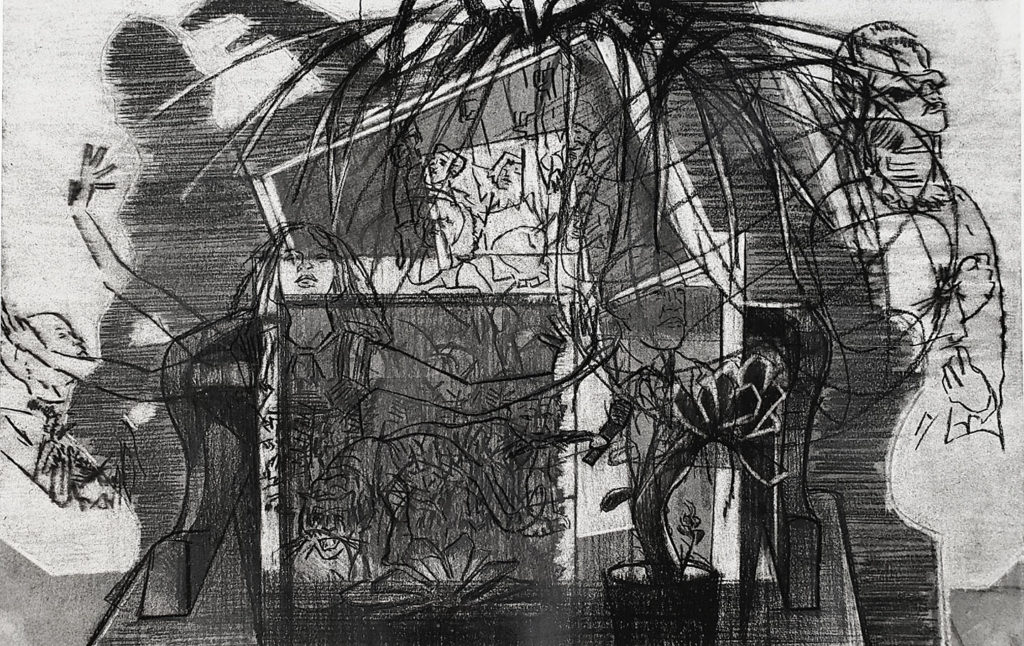

More recently, the tropical forms have divided into two separate project formats. One format is a poster graphic that can be digitally transferred within various public locations, allowing for the tropical forms to go beyond the gallery space. This format was first used in 2018 when I was invited by Kriston Chen to create a graphic for his toofprint public art project that he extended to Oranjestad, Aruba for Caribbean Link V. The second format are drawings on paper, where I combine aspects of various found objects and natural forms to create hybrid creatures. In 2019, these drawings, which became composition exercises, incorporated objects that my grandmother had collected in her home from various trips around the world. Such things as cupid figurines, conch shells, glass flowers and giraffe carvings became amusing items that were morphed and reformed within my drawing compositions. Some of these drawings were later put on display at Sager Braudis Gallery in June 2019.

How are you thinking about Tropical Forms now? Is the notion taking on a new configuration in this context of a global health challenge and restricted movement?

Right now, there are no Tropical Forms artworks in my creative space, but there are lessons learned from the notion of the tropical forms that are being applied to other projects. For example, my first tropical form was influenced by a monstera plant that lived in my Leipzig studio. The plant was put there – placed in many Leipzig studios and apartments – to create a tropical atmosphere within an interior space and provide colour during the grey winter months. That concept of domesticated tropical habitats has stuck with me. It is something that I think about every time I am away from the Caribbean. I hope to find appropriate ways to address that concept further as I continue to make work. Most recently, during quarantine, I collected tropical and subtropical plants for my apartment in Ohio. I document them in my Still Life 2020 series, along with figurines I have collected for the Souvenir project, and with graphics collected from media I consume on a weekly basis. It was a way for me to give a nod to these developing ideas when I was away from my sculpture studio during quarantine.

Another lesson learned from the concept of the tropical forms is the purpose of knowing and reflecting upon migrant stories. The story of the Cuban contract workers sent to Leipzig has been one of the most surprising stories I have encountered within my travels. That story is a perfect example of quiet histories that exist in the world, involving migrants being exported or imported to the Caribbean region. I learned about other migrant stories while working with Veerle Poupeye and Allison Thompson on the Arrivants exhibition in Barbados. While participating in that exhibition, I was reminded about how migrant stories are a central topic to the region, and I would like to engage with that topic as I approach my thesis paper to conclude my MFA programme. More immediately, I would like to start thinking about my own personal story as a migrant who continues to hop in and out of North America and Europe in order to secure opportunities. I have noted my migration through journals, blogs, and video recordings, but I have not made complete projects. While this global health challenge continues and there is restricted movement, I think it would be a good time for me to reflect on my previous migrant experiences and develop artwork from them.

This pandemic has forced a number of art institutions to explore virtual exhibition formats. I know your creative practice also includes curatorial work and, you are the director’s assistant at the Kent State School of Art Gallery. Have you been thinking about new strategies for sharing art with the public? How do we design experiences of art in a time of coronavirus?

Yes, I am also working as a graduate assistant for the Kent School of Art Galleries and Collection. That arrangement was put in place with the help of the Gallery Director, Anderson Turner, in exchange for a scholarship for my studio art studies. The arrangement continues to be rewarding for me.

I must mention that I have also been very fortunate to enjoy a comfortable summer in Ohio through the financial support of the Thomson Family Foundation in Grand Cayman, which gave me a summer stipend to continue my MFA research. I am continually appreciative of that foundation and the work it is doing for Caymanian college students. I have also been lucky to have a part-time job with my university. I have been working with Gallery Director, Anderson Turner to design an online store for student-made merchandise and also to curate an exhibition about Robert Smithson’s Partially Buried Woodshed, which celebrates its 50th anniversary in Kent, Ohio this year.

I think the future for art institutions (specifically Caribbean institutions) is looking bleak, at the moment. I have been attending webinars in the last several weeks – webinars hosted by American art Institutions and Caribbean art institutions. I have been listening and trying to become better aware of the moves and compromises institutions are making within the shock of physical distance restrictions and budget cuts. I think that there are a lot of great ideas circulating. While listening to webinars and working this summer, in both the capacity of a gallery worker and an artist, I have come to realise four things that I believe should be considered for sharing art during this pandemic:

- Websites are underrated resources.

In my opinion, a lot of institutions might be currently using their websites as digital poster boards, sharing information about their physical institution, additional text and images relating to exhibition projects, and perhaps the occasional video. With that said, website platforms have great potential these days, especially if institutions are willing to pay 50 USD or more for a monthly website subscription cost. For example, with a Squarespace website subscription of 52 USD, I was able to set up an online art shop this summer that manages merchandise inventory, runs a digital POS system to takes credit and debit card payment, calculates shipping costs for local, regional and international carrier options (that so far has not been wrong), sends out email responses, sends payment deposits to chosen bank accounts and runs an e-commerce programme that monitors website traffic and can send visitors personalised email advertisements for products they browsed and never purchased. Plus, you get 24-7 customer support options if something on the website goes wrong. Websites are great resources. I hope we do not underestimate them. - What is the cost of an online exhibition?

I see many art institutions creating virtual tours for their exhibitions. These virtual tours are being generated from realtor groups and can cost hundreds of dollars. With that said, similar virtual tour files can be generated by affordable smart phone and computer apps, allowing institutions to produce virtual tours by smart phone or digital camera. Of course, the quality of the tour images may be lower and there is more work involved, but if an institution is tight on money then perhaps, they could explore the option of creating their own virtual tours rather than outsourcing. - Do more public art.

I think institutions should do more public art exhibitions, making use of poster art, graphic designs and reproducible graphics. The toofprint project in Trinidad is a great example of an affordable public art project that can easily engage with a local community. - Use more hyperlinks!

I have begun to consider the 21st century art movements: internet art and post internet Artists in these movements seem to have a great respect for hyperlinks and their value within visual art. Artists in these movements seem to use hyperlinks as a way to change the relationship between the visual art and the viewer. Rather than having a traditional painting that gives visual references though its aesthetic, that can be assumed by the viewer, internet art directly connects the viewer to the references made in the digital visual through hyperlink. The viewer is not left assuming and is prompted to challenge the artist and join in their research by accessing reference information – similar to the relationship of an academic research paper to a viewer/reader.

Stay connected with Simon Tatum:

Instagram: @_simontatum

Website: www.simonjtatum.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.