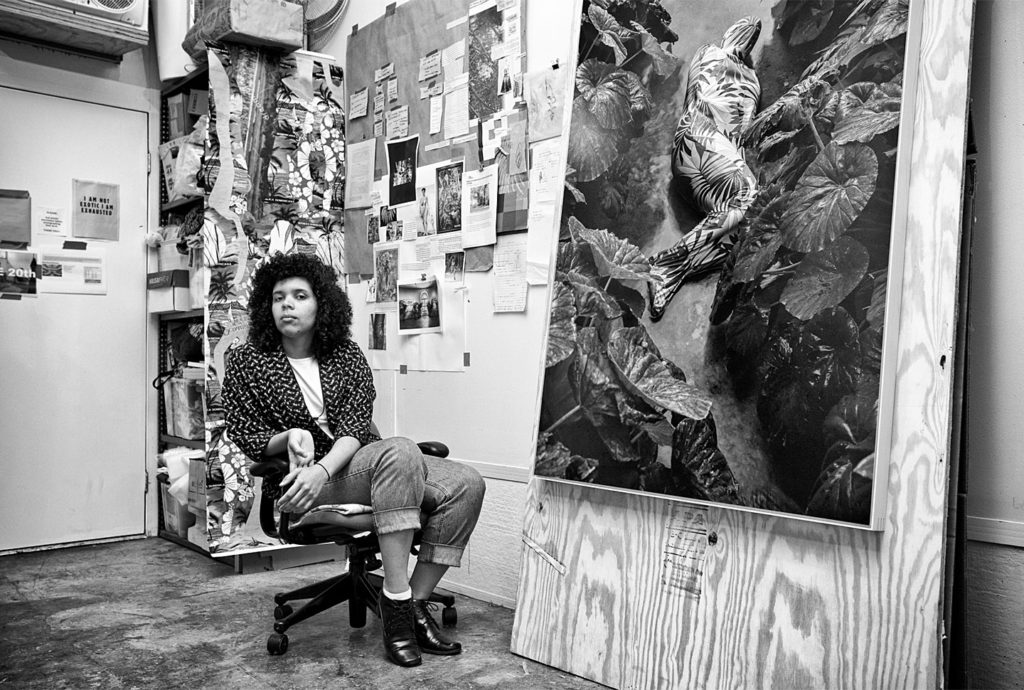

A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Joiri Minaya

Marsha Pearce: How are you Joiri? How are you grappling with the confluence of a pandemic and a global uprising in the face of racial injustice?

Joiri Minaya: I’ve been constantly overwhelmed and exhausted through the last few months. When the pandemic hit, I was about to open a solo show at Baxter St Camera Club NY, start my Spring teaching gig with the Bronx Museum, and attend the Mercosur Biennial in Porto Alegre, Brazil, where my installation #dominicanwomengooglesearch and my video Siboney were being shown. All of that was postponed or transformed into an online version in the middle of the uncertainty, at the cost of a lot of extra last-minute work in the form of many Zoom and phone meetings, loads of admin work, home video productions to replace my IRL classes.

As a member of the diaspora, one is already used to travel challenges and being far from loved ones, but the unprecedented challenges of the pandemic added a very heavy layer of anxiety and vulnerability. Closed airports, the powerlessness of having relatives hospitalised in critical condition abroad and not being able to see them, a healthcare system that feels inaccessible to immigrants / BIPOC on a normal day, let alone in the middle of this – all these have been difficult realities to grapple with. On top of everything, my passport needed to be renewed right when the pandemic started and the passports institution closed their operations, suspending all services except for life or death emergencies. For a while I was torn between holding on to my passport until the very last day of summer that I could use it, in case of any emergency travel. I ended up sending it over to be renewed in an uncertain amount of time, whenever they reopened, and accepting that, should something happen abroad, I’m not going to be able to travel in the meantime.

The racial justice movement has been a roller coaster of emotions: anger, sadness, indignation, but also hope and inspiration in seeing the breadth and depth of the manifestations and conversations during this iteration of the movement. It’s been specially exhausting, yet rewarding, to have difficult and long-winded conversations with relatives and friends in the Dominican Republic, who have a very complex relation to race and social movements. At the same time, it reminds me of the relevance of the work we do: If the beginning of the pandemic made me question the relevance of making art, the subsequent events have reminded me why it’s still important.

But ultimately and above all, I’m thankful to have freelance work and professional art opportunities still available; thankful to belong to such a resilient and dedicated community that has faced this crisis with fierceness, creativity and versatility; thankful to have the support and company of my partner and partial access to my studio, and thankful that my family abroad is, for the most part, healthy and safe.

Also, a lovebird flew in through my window looking for food and shelter on the first week of the lockdown, which I decided to keep “through the pandemic” after putting up posters and not finding an owner. It’s still around, and while it’s a mischievous and slightly aggressive creature that behaves nothing like the cute little lovebird in YouTube videos, taking care of it, along with my plants, has been an almost therapeutic distraction.

Your work was recently featured in the group show Still Here, at HUB Gallery on Penn State’s University Park campus. Tell me about your work in that exhibition. How does the title of the show and its theme of survival/endurance resonate with you in this current moment?

For Still Here, curators Larry Ossei-Mensah, Kiara Cristina and Dexter Wimberly included my video Siboney in both iterations of the exhibition (MoAD and HUB Gallery), and at Penn they also installed my wallpaper Redecode. Siboney is a video that documents an action of painting the tropical pattern from a found piece of fabric onto a mural on a museum wall for a month, followed by the subsequent transformation and partial erasure of said mural with my body as I pour water on myself and dance-scrub myself against the wall, to the beat of the song Siboney, the Connie Francis version. The work makes a parallel between the way in which both the song and the pattern are elements that perpetuate an exotic construction of the Caribbean and the black and brown female body, and proposes a re-evaluation, reclaiming and reimagining of said fantasies.

Redecode is a wallpaper I designed based on the wallpapers Martinique/Banana Leaf designed by Albert Stockdale and first used by Don Loper for redecorating the Beverly Hills Hotel, and Brazilliance by Dorothy Draper. Both designs were used in fancy, US hotels during a time when the US was actively involved in several imperial endeavours through interventions and invasions in tropical areas in the Americas and the world. I was interested in this juxtaposition of how tropicality was imagined as this vehicle for pleasure, freshness and leisure when applied to these hotel interiors, versus the realities of war and violence in tropical spaces at the time. The wallpaper in my work pixelates the original designs in an effort to disrupt representation in their visual language, and inserts QR codes among the pixels with links to content that inform some of my thoughts while making the piece.

Works by other artists in the show similarly asserted and enunciated a present and thriving African diaspora in spite of colonial frameworks, and in that sense, although the show precedes the pandemic, it almost predicts this necessity of affirming oneself when it seems that everything is operating for one’s erasure. The actual exhibition went through a beautifully designed and thoughtful transformation to the online space within a very short time after the pandemic hit, itself embodying the spirit of resilience that the works and the show proclaimed.

Amphitheatre, Miami, Florida, (2019), dye-sublimation print on spandex fabric and wood structure, 12 x 5 x 5 ft. Photo by Zachary Balber. Image courtesy of the artist and Fringe Projects Miami.

In December 2019, as part of Fringe Projects, you cloaked the statues of Ponce de Leon and Christopher Columbus, in Miami, Florida. Today, in the context of the Black Lives Movement and amplified cries against white supremacy and the legacies of colonialism, we see statues and monuments being challenged and toppled. What is the significance of the “tropical” pattern you used to wrap the statues of de Leon and Columbus?

Initially, I wanted to cover a Columbus statue in Nassau, the Bahamas in 2017 with a tropical pattern from mass produced designs – appropriating it to resignify it in a public space context, in relation to the statue. My logic was that by doing that, I was underlining the relationship between colonisation and contemporary tourism in the Caribbean, which is a massive, superficial and consumerist beast. There are so many ways in which contemporary tourism in the Caribbean traces, highlights, reenacts and even celebrates the physical, systemic and ideological remnants of colonisation. The fact that these statues then become touristic sites, visited and talked about in tours – “unmissable” stops in tour guides – is a testimony to that. The Bahamas statue wrapping didn’t happen in real life due to permit issues, but a photo montage of it was used to generate dialogue with the Bahamian audience and now there’s a small archive of about 80 documented opinions on the proposal in the form of postcards.

Two years later, I had the opportunity to really cover not one, but two statues through the collaboration with Fringe Projects Miami. For that occasion, instead of appropriating already existing patterns, I designed my own. I wanted to take the opportunity to cover these statues while also highlighting stories of resistance and resilience of the people who survived these oppressive systems. So the patterns for these two statues were designed specifically in relation to Ponce and Columbus: Manchineel, the main plant in the Ponce pattern, was the fruit of a plant used by the Calusa natives of what is today South Florida to poison their arrows, and it was due to this poison that Ponce died. Castor, the main plant in the pattern that wrapped the statue of Columbus, was brought to the Americas by enslaved people who were forcibly transported here. They had the knowledge of how to effectively use it medicinally in spite of the plant containing a very potent poison called ricin. Castor was used to heal disease and ailments in plantations, but also spiritually in traditions of “despojo” (dispossession, riddance, purging, cleansing) that are still practiced to this day. So, using this plant to cover Columbus was, to me, also a poetic way to say: “Here’s something we need to get rid of.”

Something that has been important in my work is the awareness of visual languages – what they convey, where they come from. Botanical illustrations, a style that is often evoked by these commercially available contemporary tropical pattern designs, were not only scientific documents, but tools of the empire to assess and scrutinise newfound resources that were later exploited. So, my interest in this style has to do with using that same colonial tool to subvert other colonial symbols.

I love how the social justice manifestations and conversations have not only focused on the practical, societal, systemic and political demands of justice and reckoning, but have also strongly focused on symbols like these; understanding how images and symbols are extremely powerful, in spite of giving the appearance of being secondary or symptomatic.

Your cloaking of those statues was a temporary intervention – a means to trigger reflection, conversation and hopefully lasting action. Have you been thinking about possible permanent solutions for cities, or the next steps, now that many of these offensive monuments have been removed?

Yes, I have! This moment in time has given me lots of ideas on how to address this in my work, the specificities of which are still marinating and finding shape in my head, notes and sketches. However, outside my own art, I do have some general thoughts to share around this matter. I think the most important thing is to commission new works by Black / PoC / Native American / Immigrant artists, and to highlight the narratives and arduous endeavours of the survivors, not the oppressors. Not only work by non-White artists, but also scholars, researchers, directors, institutions. And not only commissioning work but supporting those artistic visions without tokenising them – committing fully and deeply. Do we need monuments? If we do, do they have to be these representational, heroic, phallic figures? How can we reimagine what a monument is? I’m thinking a lot about the visual language chosen for these monuments. Although it has been important for me to use Western means of representation (like the botanical style of illustration that I use for plants in the Cloakings) to criticise, flip and deconstruct colonial structures, I often think about what other codes and visual tools outside of this Western canon can we alternatively use, and how to contextualise and activate these possible different languages without flattening or mischaracterising them.

I was reading about Mount Rushmore on Wikipedia a while ago, curious about whose land it was on (Lakota / Sioux) and how the idea of that monument came to exist and be executed. Not surprisingly, it’s full of controversies and ignored Native opposition. Then I read about Crazy Horse, an Oglala Lakota leader who fought against settler colonialism, and whose likeness is the subject of another controversial mountain-monument in the vicinity of Mount Rushmore: the Crazy Horse Memorial (incomplete and “in progress” for the last 72 years). Crazy Horse was a man who resisted being photographed, and asked to be buried in an undisclosed location. These refusals of representation are by themselves something to meditate on. To read of the indignation of some of the Lakota people about the monument, and how to them it is a desecration to have a mountain carved into images, for me circles back to these considerations about representation, visual languages, monuments, who they honour, and how.

Congratulations on being chosen as a recipient of a 2020 New York Artadia award. What does this support mean to you, particularly in this challenging time that has impacted artists and the arts?

Thanks! I’m a freelancer, and many of my gigs fell through or were cancelled with the pandemic and the impossibility of gathering, so this award – which under normal circumstances would have already been an honour and a temporary relief from trying to make art while being overworked – became much more impactful in the context of the pandemic. Not just economically but also career-wise; the recognition came during a moment when making art was starting to feel somewhat pointless in the face of everything going on, so it was a very appreciated encouragement during a particularly vulnerable moment. Pandemic aside, it’s a big privilege to be recognised in this big city with so much talent, and also a responsibility, considering that other finalists were also greatly talented. I feel that support needs to be honoured in the work I make!

Stay connected with Joiri Minaya:

Instagram: @joiriminaya

Website: www.joiriminaya.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.