A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Richard Mark Rawlins

Marsha Pearce: Richard, how are you holding up in this pandemic? What’s your perspective on things in the UK?

Richard Mark Rawlins: I’m holding up as best as I can in these strange and somewhat surreal times. I am doing better now than when it all started to be honest. It’s not always easy but my partner, Mariel, makes sure that I get up and keep going. Some days are better than others, but that’s life. It started like we were living in a dystopian movie with everybody alive, but just inside their homes, and we weren’t dressing like characters from Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome… and there were no zombies. In the United Kingdom we are in a sort of limbo; as is much the case with most of Europe. No one knows when we can look forward to a total release from lockdown conditions or when borders will open up again and what that will mean for travelling. There is talk of a reciprocal bridge scheme of no quarantine for countries that won’t quarantine UK travellers in return. But what that really means… well we are not sure. The rules are changing every week. We clap for the frontline workers and NHS every Thursday at 8pm with gusto, although I’ve seen a decline in the activity over the last month, as people are really getting fed-up with staying at home. Restrictions have begun easing up somewhat though, and we are now allowed to visit friends in their gardens while maintaining social distancing.

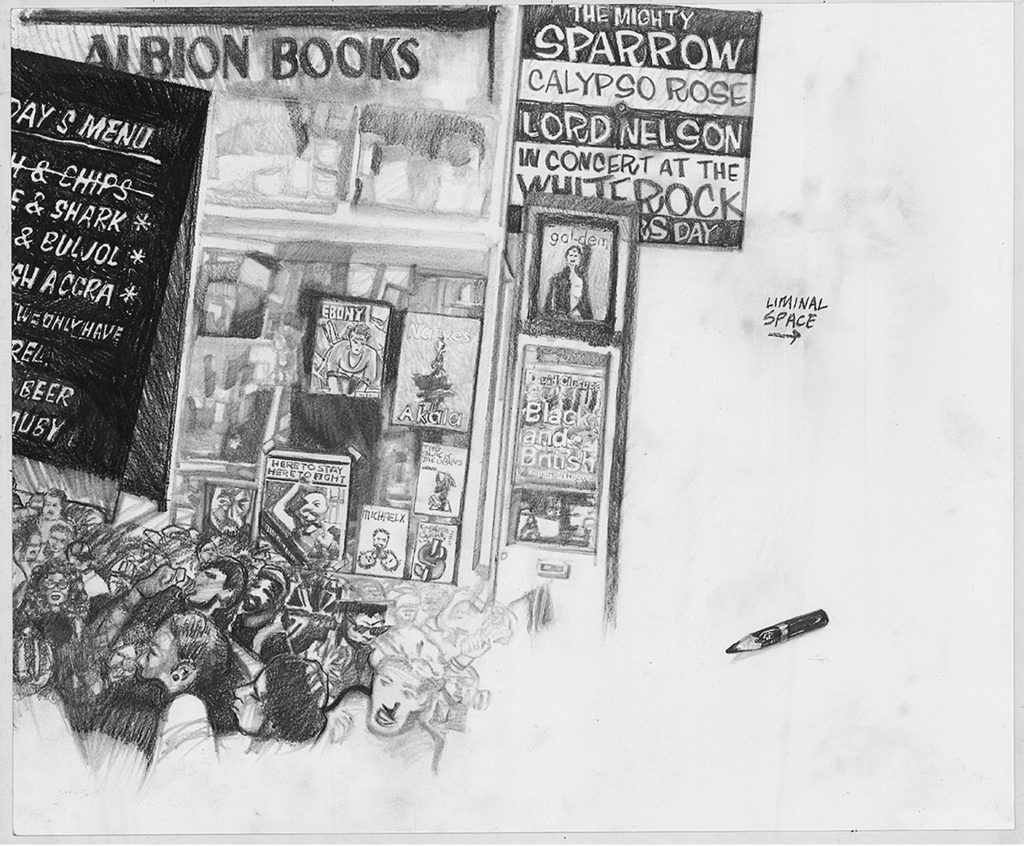

My own personal situation isn’t that bad, as compared to friends who live in London or even Birmingham, as we live in Hastings, a seaside town on the south coast. On top of the fact that Hastings has only had 53 cases at this point, I’m ten minutes away from the beach (it’s listed as one of the places with the most hours of sunlight in the UK) and there are lots of green spaces and woods and its pretty much wide open. Therefore, even with social distancing restrictions and the rules of when, how and why you can leave your home, it hasn’t been that unbearable. It’s spring here, so like most with a garden, we’ve started gardening, and that gives us immense pleasure, watching stuff grow and getting out into the backyard and speaking to neighbours to just sort of cut the isolation and, of course, enjoy the weather. I have a Naparima Girls’ Cookbook from Trinidad and spend time experimenting with Trini meals using British ingredient substitutes, reading (currently Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire by Akala, Afropean: Notes from Black Europe by Johny Pitts, Why I’m No Longer talking To White People About Race by Reni Eddo-Lodge), listening to Lou Mensah’s Shade podcast, watching English football movies, F1 documentaries, re-watching Brian Lapping’s End of Empire, trying to do some writing, working, and maintaining face time via Zoom, Insta DMs or WhatsApp with my daughters, artist collectives and friends.

Congratulations on the inclusion of your work in this year’s Dak’Art Biennale, a major contemporary art exhibition in Senegal, Africa. The biennale has been postponed due to the COVID-19 crisis but what does its theme “Out of the Fire” mean to you and your work? A press note for the event explains that the theme refers to forging or “the creation of a new and autonomous world…projecting new ways of telling and approaching Africa, in a constant dialogue and interaction with the rest of the world.” How does your art practice relate to these ideas?

One of the tenets of my work is to examine what it means to be a part of the African diaspora. For me that’s larger than being Trinidadian/ West Indian/Caribbean. It opens up the narrative around migration, experiences, ancestral memories, nationhood, identity, personal lived experiences and evolving contexts. In a sense, wherever people of colour are in the world, we are part of a diaspora. For some of us, a diaspora of a diaspora, and others, a diaspora of a diaspora of a diaspora. I see the theme as meaning that Africa is wherever it is, when it is, and needs to be. I liken it to the description of an avatar in flux. In Hinduism, an avatar is described as a manifestation of a deity or released soul in bodily form on earth. It’s how I see the African diaspora as something within my work and me. I explore what that means. Because to study that helps me find me.

I want to stay on the subject of your identity. I remember your Finding Black exhibition in 2015, which gave insight to the various sources – television shows, comic books, music and more – that have fed your construction of self. How are you thinking about black identity in this charged moment triggered by the recent killing of George Floyd in the U.S. – a moment in which the pandemic of black trauma is spotlighted, and racism has been described as a deadly virus?

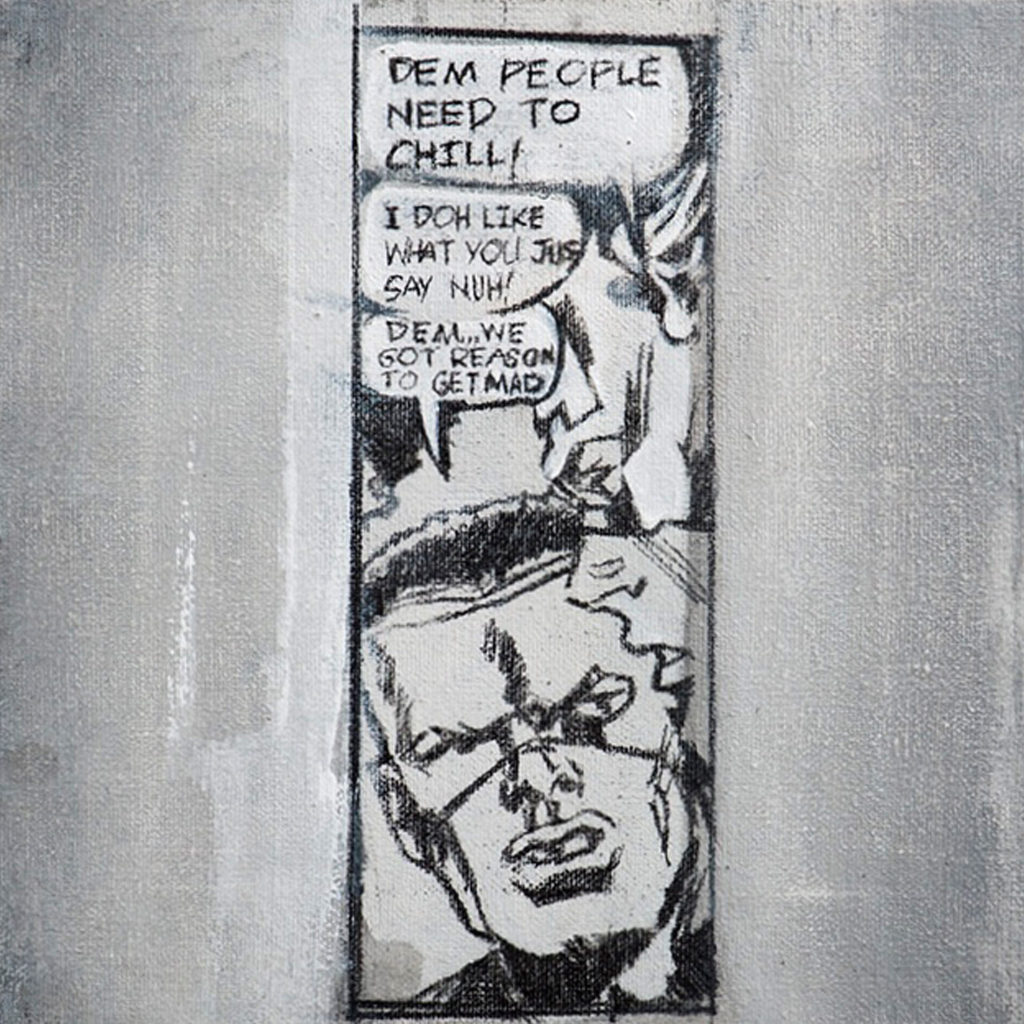

When I created Finding Black, it became a mental mood board. It was this jump-off repository of where my work would be headed. Traces of it are still in the DNA of everything I do today. It walked out the gallery and into subsequent exhibitions, and later into my dissertation as well. It’s like a spine. I keep it close because I have no choice in the matter. I remember someone at the time coyly or maybe annoyingly asking me: “Did you find it? Ha ha.” That question was an intimation of things that make one uncomfortable. It was a response to the word “Black.” Talking about blackness makes a lot of people uncomfortable. It was the most uncomfortable work I’ve ever made but it was something I needed to do. Ours (Trinidad and Tobago) is one wherein narratives of identity are often conflated with other places and other things. Eric Williams, our first Prime Minister, stated: “A nation like an individual, can only have one Mother. The only Mother we recognize is Mother Trinidad and Tobago and Mother cannot discriminate between her children. All must be equal in her eyes.” Of course, the rest of his statement, as we know, is that there is no Mother Africa, No mother India, No mother China, No Mother Syria etc. I found that problematic in searching for myself. One of my friend’s last name is Chen, another Boodan, and my own is Rawlins. My mother’s name was Walker. So, the notion of me being a motherless person only shaped by colonialism and cultural imperialism didn’t work for me. It basically heralds the idea of being “Trini to the bone” and forgets everything else. It supports “Sweet T&T a Rainbow Country” and other myths.

The notion of daring to search for my identity, “my Black identity,” and what that means, was and is still a joke for one friend of mine, and maybe for others at home, and often elicits eye rolling. Our Trinbagonian-ness is all that matters while we ironically consume American brands, television, sports, movies, English Football and, for people my age, an education rooted in a British system. It can leave one lost. I didn’t just start here in this moment, in this place. I “feel” and things resonate with me, and as difficult as it was then, researching a timeline of a life and matching it with historical and cultural signifiers while making Finding Black, it is as difficult now realising that some of the things that shaped me historically, some of the referenced signifiers, uncomfortable globalised discussions of race, Blackness, Anti-Blackness, moments of solidarity and reflection seem to be in a never-ending loop where the past comes full circle and truth to power needs to be spoken – again and again and reset. It is tiring. Some at home would argue that it has nothing to do with us. I come from an island-state that gained its independence in 1962. I have never known “White” rule.

Earlier this year you started a series of intimate photographic portraits. With social distancing and self-quarantining, I imagine you have had to put a hold on this work. Tell me about it. Are you rethinking its form and execution?

Well, like everything else, at this time I’ve had to put that on hold. Luckily, I had begun getting into the work in February and I had completed quite a few of the portraits. The project was never going to be short-term in any case and would have required a bit of travelling (lockdown restrictions have dampened that somewhat).

I had already secured many participant confirmations and was scheduling appointments with them when the lockdown hit. The second phase would have seen me conducting interviews later on in the year. It hasn’t changed the work much other than scheduling obviously, but it has allowed me the time to ruminate on the content of the interviews and questions that I’d like to pose. Also, I doubt that the work will be the same in terms of my expectations of it now, post-COVID and this current moment of unrest that we are seeing taking place in the United States, as this will obviously have an impact on discussions, and in some ways reshape the work. I think that in the long run that’s okay. It’s the nature of an art practice. Work evolves with time and a certain flexibility is necessary. So, in a sense, this pause is good for what I am creating in the long term.

You were in discussions to work on a few projects this summer for a London-based arts charity, yes? You were also set to have work shown in a UK summer exhibition. What can you tell me about these projects? Are they still in the works? How has the COVID-19 context affected plans?

These projects have been put on hold for now. I started the year thinking this is going to possibly be my “Annus Mirabilis” and then WHAAAAM!! But as my friend Sheena says: “It’s not just you Richard. It’s the whole world feeling like that.” So, you know what? Suck it up. Everything is still on and plans have been put in place to come out of the gate running, whenever lockdown eases up or the “new normal” sets in. One of them (the Summer show), has been rescheduled to January 2021 and the other project is keeping tabs on when it’s safe for us to continue, as that will involve a lot of face-to-face interaction. But “new normal” or not, I’m fully committed to both projects, even if they require some sort of adaptation. I think we are all in a bit of stasis with good reason and the “new normal” will mean adjustments. Currently, art institutions and schools are shifting graduations and final shows; some going online as a means of continuing, some have cancelled them outright, some exploring options – often to the benefit of themselves rather than the students. Many artists, as well, are trying to adapt. Some are coping better than others and, for some, it’s not that easy. The UK Arts Council has stepped in with grants – for those who have lost income because of the crisis or have had work postponed – as a means of easing the burden for those eligible, and while that funding may be stretched very thin, other organisations have also stepped in to create funding for those in need of it.

Richard you’re always producing work – adapting to contexts, space, material and equipment constraints. Obstacles don’t seem to keep you from your art practice. What are you working on in this challenging time?

My father had an attitude that was shaped by something he would always drum into us as children: “I cried because I had no shoes and then I met a man who had no feet”. Luckily, my studio is in my home. For me, that is always a requirement as I often work at odd hours. At this time, it’s a bonus, as I’m not cut off from producing and that’s important to me. As part of my plans for this year, I would have been doing a series of public performance interventions centered on the black body in public spaces during the summer, once the weather warmed up. With the almost certainty of a curtailed summer or a summer of lockdown restrictions still in place, I started exploring the idea in my studio space as a means of research and practice for when the time comes, and out of this has come a new series of photo-based works. I also finished off a drawing that I worked on practically all of 2019 and had it scanned. I am currently in the process of assembling it to its 50ft plus size for output as a full-size print at some later date. I’m also painting (well, trying to paint anyway). The object for me is to just keep busy and see how this all plays out. But honestly speaking, it really is hard to focus right now work-wise – between what’s happening across the pond, monitoring what’s going on with my daughters and family in Jamaica (one daughter is at the University of The West Indies, Mona Campus, waiting to go home) and following the politics at home in Trinidad (to sanction or not to sanction). I grab the moments of focus when they come. Some days, it’s easier to do than others.

Stay connected with Richard Mark Rawlins:

Instagram: @rmraffinity

Website: richardmarkrawlins.com/

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.