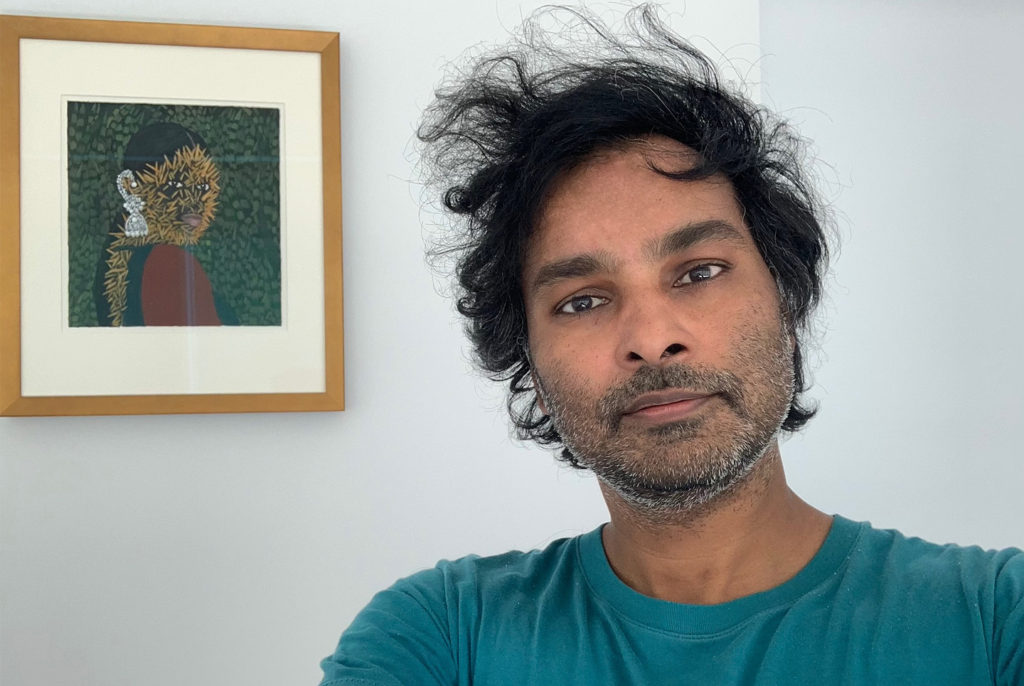

A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Andil Gosine

Marsha Pearce: Hi Andil, how are you doing? How are you navigating our current context, which has been described as a “perfect storm”?

Andil Gosine: This past week (June 15-22) has been my best since the beginning of quarantine. COVID-19 forced a very intense contention with the difficult truths of power. Among those in “my world” of family, friends, students and colleagues, the differences between those who had the virus and who didn’t, between who had to keep working risky jobs and who could flee the cities for country homes, and between who felt afraid to get sick, to die and to access treatment, and who felt invincible, whose biggest challenge was boredom, fell so starkly along lines of class and ‘race,’ in an unbearable way. I mean you know that’s how the world is organised, but something like Coronavirus comes along and strikes you hard, up close, in the most intimate way.

Quarantining in Toronto was barely different from my normal life here. At the bleakest of times in those three months, in terms of both my own mental and physical health, however, I felt genuinely lifted by the people with whom I was engaged. My friend Mélissa Laveaux, a Haitian-Canadian singer-songwriter based in Paris, and I became more ensconced in each other’s lives. We were sharing recipes and cooking “together” almost every day, had weekly Insecure watching dates, and most necessary of all, we commiserated with grief and humour over the ways in which the effects of the virus unfolded along these lines of power. When the Black Lives Matter protests started, I felt a rush of mixed emotions: anger at the continued exercise of anti-Black racist violence, but also relief that power was being called to account. The protests felt like a release from the worst feelings of hopelessness during quarantine. That we began to see some of the impact of the protests this week, and that it included the Supreme Court rulings refusing efforts to curb LGBTQIA+ and migrant rights, made it a good one.

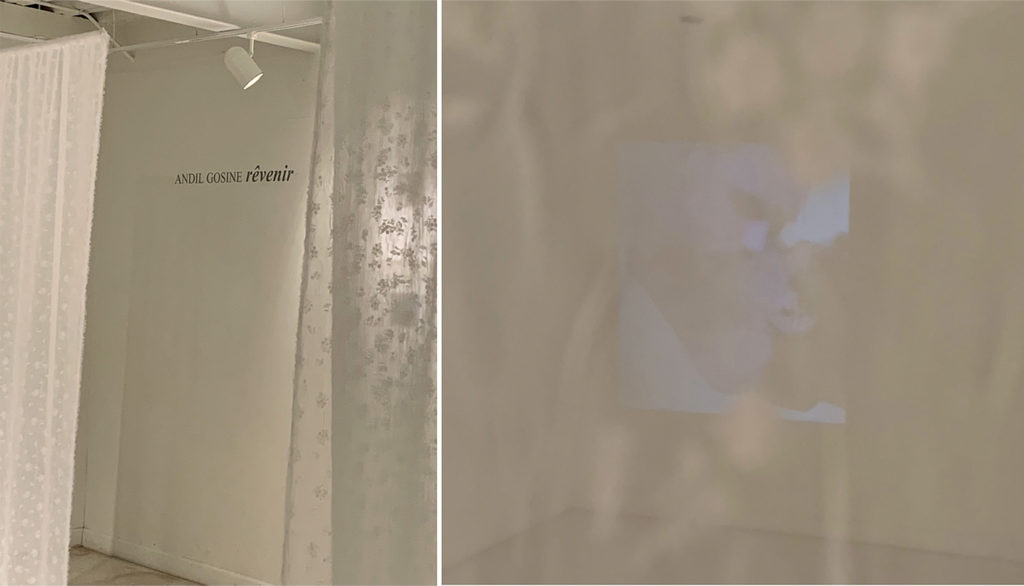

As health officials called for face masks/coverings, I recalled your exhibition at Medulla Art Gallery in Trinidad. It was held in February this year – a few weeks before global lockdowns – and it featured a number of veils, which both concealed and conveyed your artworks. Your choice of hanging fabric was inspired by Indian head coverings? Tell me about the significance of the “coverings” seen in your exhibition and their role in ideas of intimacy versus distance, and acts of hiding and revealing.

The curtains have everything to do with that thing many of us feel deprived of through the pandemic: touch. The sways that curtains make from being struck by a light breeze: that image, for me, best captures what the most desirable caresses feel like. Breezes were not an uncommon subject of conversation growing up – we love our trade winds, don’t we? – and a ranked geography of them still exists in my head. I know the best spot for breezes is my Auntie Tutin’s patio at the top of Sum Sum Hill in Claxton Bay, Trinidad. Soft breezes seem to collide in the most sensational way there. For me, there is also something foreboding, almost quietly treacherous, about the lilt of a curtain in a light breeze, a revelation of the truth that even desired caresses can take you to dangerous places and bad decisions.

The lace fabric I chose for those curtains are nearly identical to the ones at my paternal grandparents’ house in Tableland. My grandmother, Jasso, used the same fabric for her “ohrni,” the headscarf that Indian women of her generation used to wear. The ohrni is a remarkably complex veil because of its striking ambivalence. The sheer fabric that women used in Trinidad undercut the “modesty” and/or shame about the female body that the veils were often supposed to convey, and paralleled their savvy negotiations of social power relations at that time. The ohrni hides and shows, and complies with and challenges power, all at once.

There is a parallel, too, between the notion of a see-thru veil and arts practice. The two artists that have been most formative for me, both intellectually and in form, are Lorraine O’Grady and Félix González-Torres. Both are exceptional in carrying out what I think is art’s primary function: they explore and express the most difficult truths of the human condition through critical self-reflection. Each artist expresses those investigations quite differently in practice. When you look at González-Torres’s body of work, you know that, as he has said, the only audience he ever thought about was his lover. You feel the intimacy conveyed in his entire oeuvre. O’Grady’s works, on the other hand, foreground her brilliant theorization of the social history of the Americas; but as much as she investigates and implicates herself, she doesn’t quite expose herself in the same way as González-Torres. I think I’m caught between these pulls, of wanting to allow myself that confident expression of vulnerability, but as a consequence of my particular post-colonial, Anglo, Caribbean education and academic trajectory, trained like her to present more formally, to always keep some things veiled. There are different pressures of “respectability” on them of course, as a result of sexism and racism. It is hardly unusual for gay male artists like Felix to be so intimately naked, but there are a whole lot of other pressures for Black women. The ohrni-curtain-veil is my acknowledgement of that tussle, of expressing my own frustration with not permitting myself expression of the kind of vulnerability that I think would, in my case, produce better art.

I want to talk about your curatorial practice. You’ve curated a new exhibition of work by Trinidadian artist Wendy Nanan at the Art Museum of the Americas (AMA). However, given the COVID-19 context, you had to re-imagine the launch of the exhibition in a virtual format. I was happy to attend “A Literary Tour of Wendy Nanan” via livestream. Please tell me about the process of translating the launch experience online and your efforts to design virtual programming to accompany the show.

A fever, dry cough and throat ache kept me from boarding the flight to DC to complete installation of the exhibition at the AMA. I have been working with Wendy since 2016 and putting together this show has been a labour of love. Her work is so original and important. Through her art she explores core questions about our Caribbean existence, especially on the subjects of cultural hybridity, decolonization, gender and sexuality. The exhibition has been extended to the end of the year, and Wendy Nanan will be presented as soon as the Museum is allowed to reopen, but yes, in the meantime, I curated “#WendyNanan” as an online exhibition. We did some of the expected things like share images of her work on the various social media platforms. I had to make a few difficult decisions: Initially, I didn’t want to post the video I made that documented the creation of her newest sculptural installation, Breath, as it was really meant to be shown with and not apart from the work, but the museum pressed and I acquiesced (and things turned out fine).

With the “literary tour” – thank you so much for being a part of that, and I hope we hear your important, critical voice engaged with the exhibition at another juncture – I treated it as akin to an “opening,” one which would help to create a sense of community and connection. I called upon three poets who are part of her cultural sphere in Port of Spain [Trinidad’s capital city] as a way of underlining how committed Wendy is to the rootedness of her practice in Trinidad. Shivanee Ramlochan, Des Seebaran and Andre Bagoo crafted brilliant ekphrastic poems in response to her work, and we were so excited by the response to the effort that a commemorative series of chapbooks are being produced from the tour.

You’re a Professor in Environmental Arts and Justice at York University and you have been vocal on social media about the need for institutions of higher education to redress racist operational measures. What do you see as some of the structural changes needed?

Everything, beginning with access, curriculum, hiring, fair pay, and over-policing on campuses. I would underline that it is not a matter, as many white folks often pitch it, of doing anyone favours; it’s a matter of making the system less rigged in favour of them, at every vantage point. The genocide of Indigenous peoples and the enslavement of Black people are so foundational to the making of the Americas and our institutions, including the university, and we are only a few decades in after essentially 500 years of colonization—in Canada, the Queen is still the Head of State so I am not sure the project has even begun here or that we are trying to make it begin. We are very early into this process of unmaking institutions that are invested in the project of white supremacy, so not surprisingly, the list of tasks is long. I’ll give you one very small example of what I mean, although I could fill books with an itinerary of the mechanical execution of racist and classist power at the university. During my doctoral degree, I had designed a course called “‘Race’– Racism and Environmental Justice.” PhD students were allocated two teaching slots for courses at the time, but the only way of getting to teach one was to get a tap on the shoulder from the program director or being championed by one of the senior academics. Even if I wasn’t averse to putting energy into networking—I’d rather just do the actual work—mentorship was simply not available to non-white students anyway. Instead, and with the support of students and our union, we fought for it to be an open competition, at least to put a process in place which does not require ingratiation at the mercy of the old white boys, or now, also, “old white boys and girls,” networks.

The spaces you and I work in, academia and culture, are additionally challenged by the fact that notions of quality and merit are very fluid. The first time I sat on a hiring committee, we produced a different short list each time we met, because there were so many different ways to measure “merit”—and frankly, most of those times, networks inevitably benefit the already most privileged, and that’s even when there is an open competition. My university tends to favour an open competition which is unlike, I understand, the norm at North American schools. Similarly, the market-centred drive of the art world makes it extremely challenging for “outsiders” to succeed, as so much rests upon the tastes and whims of the wealthiest and, therefore, established practice. A great deal has to happen in both the worlds of art and academia to produce something resembling a fair shot to people who are Black and other non-white working class, because that is absolutely not the case now.

We are seeing intersections of the Black and LGBTQIA+ communities in protests against inequality. Do you see the Black Lives Matter Movement as having ripple effects for marginalised people, in a broader sense?

Even as the core struggles against institutionalised police violence continue to be fought and will certainly not be easily won, the impact of BLM in social and cultural realms is far-reaching. BLM has forced both a serious reckoning with the foundational original sin of the Americas (all of it), and anti-Blackness globally. As is evident throughout history, black civil rights actions advance all human rights—there would be no gay rights without the template, strategies and victories of black civil rights movements, and of course because of the central and critical role of LGBTQIA+ activists of colour across them. I feel hopeful that the persistent orientation of queer culture around the white, cis male subject will be interrupted and displaced.

Black Lives Matter is the most important and most hopeful movement of my lifetime, and the itinerary of changes that these incredibly brave young men and women have sparked and achieved will continue to be counted for years to come. In short: I am in awe, I am full of appreciation, and I feel a new kind of faith and emboldened camaraderie. I have seen it happen all around me already: we can speak to the denial and denigration of our humanities with new force, and with less loneliness in white-dominant spaces. Black Lives Matter has given me–given the world–new breath.

Stay connected with Andil Gosine:

Instagram: @andil.gosine

Website: www.andilgosine.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.