A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Mark Jason Weston

Marsha Pearce: Hello Mark, good to connect with you. How are you doing? How are things in Philadelphia?

Mark Jason Weston: Hello Dr. Pearce, thank you for giving me the opportunity to participate. The question of how one is doing is now heavier. We are floating in a new reality and I’ve been reading differently, watching too much news, and trying to navigate, as best I can, days that seem to bleed into each other. The way we experience time has definitely shifted, and I’m trying to use that to my advantage as it relates to the new work I’ve been making in quarantine.

Philadelphia, and the state, did a good job in their response to the pandemic, but there is a disconcerting number of people who don’t seem to be taking the threat of this virus seriously. I’ve seen too many people in public not wearing masks and not socially distancing.

Your latest collage works are posted on social media, accompanied by #theblackbodyastext. Please tell me about these artworks. How do you understand the word “text,” and in turn, how are you thinking about the Black body in relation to this word – particularly at this time of heightened awareness of the injustice meted out to Black and Brown people?

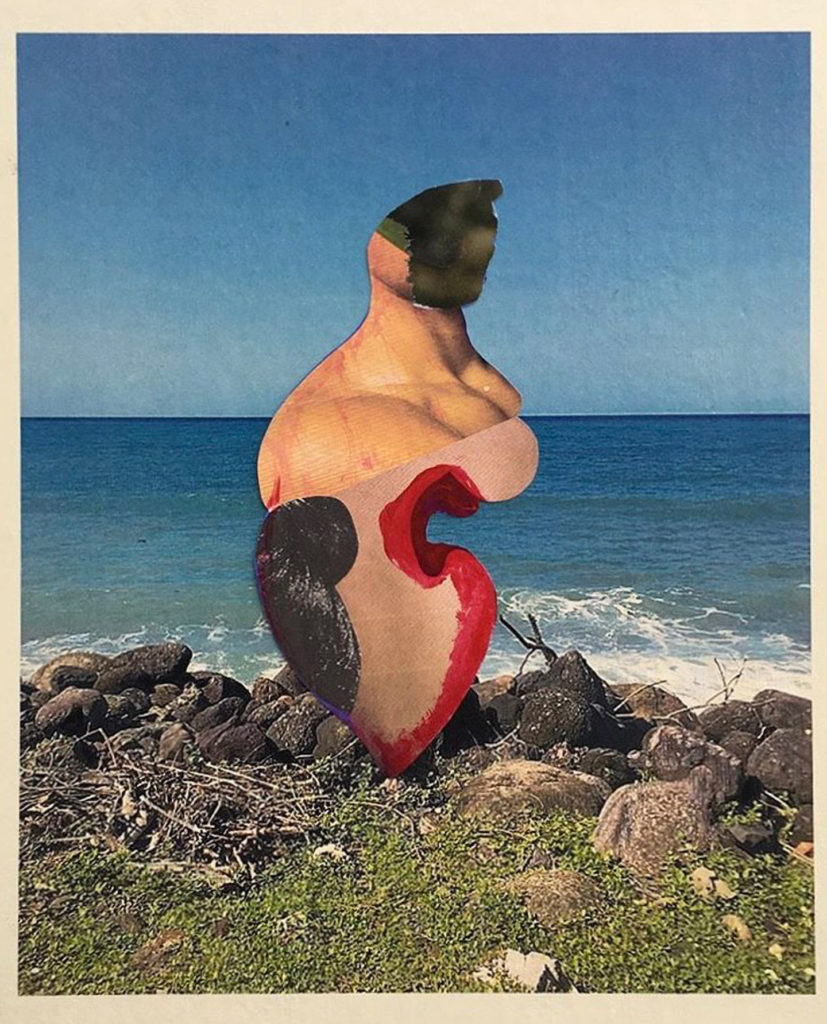

The recent pieces I’ve been sharing on Instagram with #theblackbodyastext is a response to the current social and political landscape here in the US. I’m still thinking about it as I go, but I’m trying to understand why Black, Brown, queer and any person deemed “Other,” can still be denied their humanity by the ones who benefit from white supremacy and structural racism. I suppose the answer is obvious, but I continue giving it my attention. I understand the word “text” as any object, or site, that can be read. The Black body can be seen as a site of / for scrutiny. From the beginning, the white gaze has been about reading/misreading and scrutinising the Black body without considering the rich, unique humanity it contains. These recent pieces, I think, are trying to retake control of the narrative at this time when people are paying real attention to the injustice suffered by Black and Brown people.

In 2018 you produced some images that seem to carry special resonance in our present context. I am referring to the works you labelled “White Supremacy,” “Blind to their Privilege” and “Deep, Slightly Loving, Side-Eye to a Particular History.” I would love to hear about your thinking at that time and perhaps how you see those images today – a year in which we are reckoning with history, privilege and white supremacy.

Those three pieces from 2018 do appear to resonate at this moment. It’s hard to say what my thinking was at the time, but we were two years into the Trump regime, and the hard realisation was starting to set that we were in serious trouble. It was also a time when not a day went by without news of another Black or Brown person brutalised and/or killed because their humanity was denied or not recognised.

I came across a statement you made. You said: “Collage is a kind of delicate butchery: a way of inducing nostalgia for moments that never happened.” What can you tell me about the roles of “visual violence” (to appropriate curator Ida Højgaard’s term here) and longing in your collage practice?

My statement at the time was very much tied to my poetry practice and wanting to expand, go beyond the page, and “write” poems visually. Thank you for introducing me to Ida Højgaard and her term “visual violence.” I could be wrong, but I read that term as a taking back of control, of agency, in how the story of Black and Brown people are told. “Visual violence” and longing are central in my collage practice. Thank you for pointing it out so succinctly in a way I’ve never noticed before. In a previous life I was a butcher, and I made the statement at that time. It is also the reason, that for better or worse, cuts of meat appear frequently in my images. In my mind, longing is a central part of the human condition, because we are never truly satisfied.

Yes, Højgaard uses “visual violence” to talk about how violent actions in artworks can be counter discursive; how those actions can be transformative and serve as elements of resistance. I wondered, therefore, about acts of cutting in your collage work and their significance for you. It is interesting to learn that you were a butcher! Let’s talk about your other practice. You mentioned your poetry and your want to expand it beyond the page. Trinidadian poet Andre Bagoo says poetry “is not confined to the page but sneaks into music, prayer, and the spaces we congregate in, our shared tongue.” Do you agree with this perspective? Is there a dialogue between your poetry practice and your visual art making?

I admire Andre Bagoo’s work, and look forward to reading his new collection of essays, The Undiscovered Country. I agree with his statement about poetry. Our problem is we too often resist acknowledging the truth of it. Poetry is always there, dancing in the details of all our endeavours, so I continue to listen to the dialogue between my poetry and visual practice.

Stay connected with Mark Jason Weston:

Instagram: @markjasonweston

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.