A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Olivia McGilchrist

Marsha Pearce: Olivia, so good to connect with you. How are you coping and processing these times in which we find ourselves? Have you been able to stay in touch with family in Europe and friends in Jamaica?

Olivia McGilchrist: Thanks Marsha, it’s a real pleasure to reconnect, and I’m grateful to be included in this inspiring conversation series, as I’ve learned a lot from the previous interviews – both from artists I know and artists I’m glad to have discovered. Thank you for taking the time to do this. It’s late June 2020 at the time of writing, and things in Montréal, Canada have opened up in the last few weeks, apart from the universities and libraries where I was spending most of my time and having the majority of my social interactions. I’m grateful for the safety and comfort of my home, the love and support of my partner (and our cat!) but this is definitely a challenging experience.

Being at home so much has taken its toll on my sense of being grounded here. Am I being useful and supportive to those around me? What could I do better each day? Since I’m far from family and friends (in Jamaica, the UK, France and Switzerland) this has been a time to reconnect with them online; to value the bonds with loved ones, friends, and colleagues while making new contacts through different online platforms. But if air travel remains limited, how soon will I able to visit my Mum, and what happens if she needs my help at short notice? Time and space have shifted so much for many of us, and this evokes Puerto Rican writer and scholar Carmen Beatriz Llenin-Figueroa’s literary method which is inspired by the action of walking and adopting a rhythm of “extremely slow time”1 in her analysis of Barbadian poet and historian Kamau Brathwaite’s “tidalectics.” Perhaps we need to consider this more seriously now; making the necessary changes in our lives that can allow for this.

How is your PhD research coming along?

Since 2017, I’ve been pursuing the Individualised PhD at Concordia University with Professors MJ Thompson, Lynn Hughes and Alice Ming Wai Jim. I’m grateful for this supportive committee. The current proposed title of my thesis is: Virtual ISLANDs: postcolonial hybrid identities in Virtual Reality, which will change as I write and create. One of the things that inspired me to apply for this programme was your 2015 call for artists’ proposals to answer this question: “What might a Caribbean future look like?” As I go back to your document, I now realise that my explorations in virtual reality (VR) and video are in dialogue with some of the propositions you offered in your call, such as these strong images:

“What if, instead of nests connected by sea (a potent image of nests or husks floating in the sea can be found in Annalee Davis’ 2008 video titled I Celebrate the Chorus of the Creole Chant) the islands were reimagined as weightless mounds hovering in the sky, bonded by cumulus vapour, or as a wireless network of nodes in a digital cloud? Is the future visualised as an ideal or is it to be seen through a dystopian lens?”

The PhD is moving forward. I am now a candidate (I passed my comprehensive exams, and my thesis proposal was accepted) and I’m now starting my written thesis and making progress on my artwork. However, since March, things have changed a lot. My VR research-creation work [research-creation projects combine creative practice with scholarly investigation] now exists in a different reality. The artwork created so far comprises physical video installations with a component for a VR HMD (head mounted display). Due to the global pandemic, both these artistic methods are in question and VR HMDs to be shared by different viewers have become a health hazard due to the HMD’s placement on the viewer’s face and the fact that most VR goggles cannot be cleaned effectively between viewings in rapid succession. In contrast to these display strategies, available consumer-sized screens (laptops, phones, tablets) have become the main space in which my artwork can be experienced. Should I be concentrating on this if I want to make my work accessible? That’s a daily question at the moment. And also learning how to engage with Instagram better – I’m still learning, slowly.

The recent exhibition at Studio XX, titled Some Ellipses, featured work by you and the Black Quantum Futurism Collective (artists Camae Ayewa and Rasheeda Phillips). Please tell me about the work and the show. How does it resonate in this moment in which the lived realities for so many, are being resisted?

I want to thank the entire team at the Montréal artist-run centre Studio XX for making this possible: Natacha Clitandre, Roxane Halary, Stéphanie Lagueux, Hannah Strauss, Deborah VanSlet, Claire Moineau and Orphee Russell. I also want to thank North American artists Rasheedah Phillips and Camae Ayewa from the Black Quantum Futurism Collective for being open to adapt their physical installation to the current online format, and Canadian author Marilou Craft for writing a beautiful text about both our projects. It was also really inspiring to have an online conversation with Rasheedah Phillips, moderated by Hannah Strauss on June 18th.

To learn more about the Black Quantum Futurism Collective’s project entitled Black Womxn Temporal Portal (The Future(s) Are Black Quantum Womanist), here are the links shared by Rasheedah Phillips after our artist talk:

https://www.blackwomxntemporal.net/

https://www.blackquantumfuturism.com/blog

https://www.blackquantumfuturism.com/shop

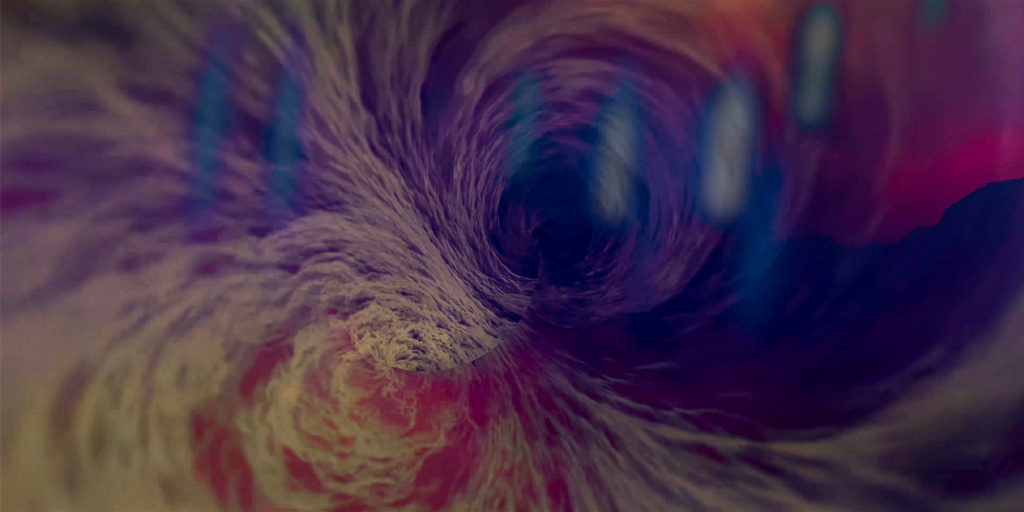

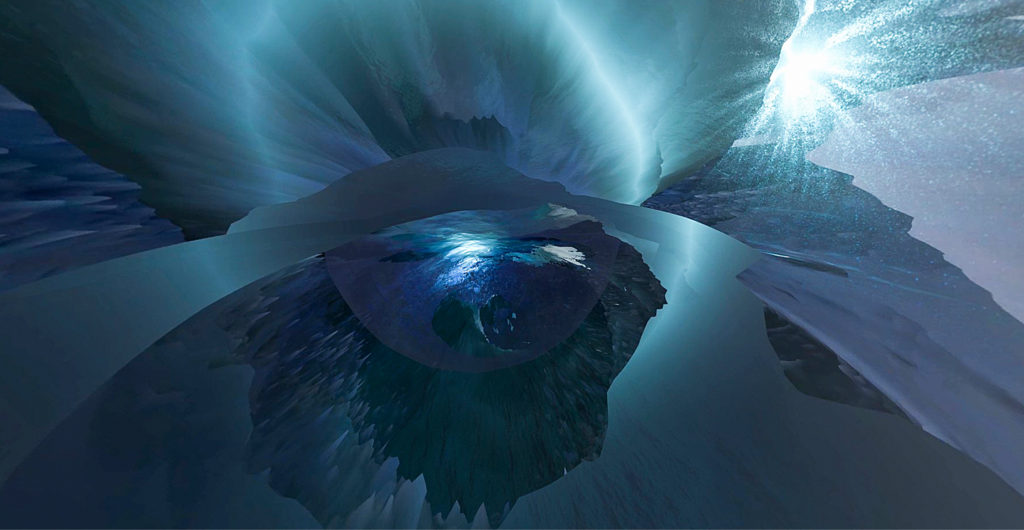

In my work, entitled X-cosmos-X, I am looking at water and submersion through screen-based technologies, to stimulate a contemplative, immersive experience. Inspired by Kamau Brathwaite’s notions of “tidalectics” and a “Caribbean cosmos,” I use layers of video and 3D water animations to create a fluid effect, further pushing my explorations in experimental, virtual, underwater environments inspired by the Caribbean. My proposal for this show was a site-specific installation, and the work was still in progress in late February. By mid-March, when it became clearer that this wouldn’t happen, I shifted my focus to create a series of videos that invest the exhibition’s side-scrolling webpage in a meaningful way.

In terms of how the projects resonate: hopefully, both of the works in this online exhibition can offer a space for thought, engagement, an opportunity to visualise an alternative past, present and futures; getting immersed via a screen in another way. Can your computer or your cell phone become an exhibition space while you visit the website? It might also prompt new audiences to feel included within art spaces.

I know you have an interest in Afrofuturism. As the Black Lives Matter Movement reverberates in this time, thoughts about possible futures are a critical part of the conversations. I can’t help but think of artist Alisha Wormsley’s recent billboard with the words “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE.” It is so powerful. What future are you hoping for?

Yes, I have been researching Afrofuturism, and I’m inspired by the definition by British writer and artist Kodwo Eshun and American ethnomusicologist Wayne Marshall’s reading of American scholar Louis Chude-Sokei.

According to Eshun: “Afrofuturism studies the appeals that black artists, musicians, critics, and writers have made to the future, in moments where any future was made difficult for them to imagine […] Afrofuturism, then, is concerned with the possibilities for intervention within the dimension of the predictive, the projected, the proleptic, the envisioned, the virtual, the anticipatory and the future conditional.”2

And Marshall observes: “Afrofuturism may function differently in varied contexts of racial formation, and Chude-Sokei’s critique heightens the need to explore Caribbean contexts and trajectories for such ideas.”3

Thanks for mentioning Alisha B. Wormsley’s work! Wormsley’s billboard is powerful on several levels. On her website, her project is described as: “THERE ARE BLACK PEOPLE IN THE FUTURE is an afro-futurist interdisciplinary body of work; video, prints, collages, sculptures, and most recently, a billboard.” The billboard creates a visible space of contestation in a society where this statement needs to be heard, seen, and repeated. Reading the artist’s thoughts in an interview with Keisha N. Blain was really helpful to understand her motivations for creating this work, and how it developed in relation to how it was received in the local community: rejected by some; embraced by many more. With her various projects, I’m inspired by Wormsley’s capacity to engage with so many different Black voices, so many different perspectives on Black experiences in America, which can resonate with many Black communities around the world.

The Black Lives Matter movement is incredible. I’m really hoping more people can understand the importance of present actions for Black liberation, equality and freedom within historical, political, cultural, theoretical and aesthetic developments of the last centuries – both across the Americas, including the Caribbean, Africa and Europe. The histories and realities of anti-Black racism globally are complex and need to be understood from different perspectives.

Regarding the future I am hoping for, this concern informs my PhD research-creation project. Yet, I find it challenging to formulate a concise and practical answer today. I am reminded of American artist Arthur Jafa4 quoting Korean artist Nam June Paik: “the culture that will survive is the culture that you can carry around in your head.” I am hoping for a future where each person is aware of their own culture(s) and of its legacies within a global context; where each person can carry their culture(s) around; while respecting and learning about other cultures and cultivating solidarity.

You mentioned legacy; I want to talk about that. Your practice includes experimentation with video installations and virtual reality (VR) technology. As the world confronts asymmetries of power and the residue of colonialism, do you see colonial legacies extending their reach to technology?

My ongoing VR artwork offers viewers two forms of engagement where virtual immersion is related to the experience of being in water. Viewers will be able to navigate between virtual islands or remain still amidst a virtual tidal wave, represented through 360 videos and 3D animations. This project invites a reading of VR practices, towards aesthetic/artistic aims, through the exploration of submersion as an alternative notion to describe VR’s immersive experience.

I approach VR technologies within a continuum of lens-based media emerging within modern European colonial projects; their capitalist empires relying on maritime transportation technology; and the financial value colonists ascribed to the free labour they oppressively obtained from enslaved people. This has led me to research the inherent colonial bias in the mediums of film and video games; mediums redeployed within the VR production I engage with. My project aims to study virtual reality from intersectional perspectives, while addressing my privilege as a white VR artist who gains from new findings in a medium operating within what Canadian scholar Nichole Lowe describes as “registers of whiteness.”5

There seems to be a need for a shift in thinking with respect to technologies such as VR. How can we decentre Western understandings of such technologies?

I really appreciate your formulation of this question. I’m still working on how to achieve this in a meaningful and realistic way as an artist. Building on research into the central role of water in Caribbean cultures, my PhD project is informed by the violent histories of transatlantic slavery and Atlantic modernity,6 through the framework of British scholar Paul Gilroy’s notion of the “Black Atlantic.”7 In combination with creating an artwork using research-creation methods, my theoretical research attempts to develop a critique of VR mediums, paying close attention to selected VR works presented in artworld and film festival contexts. This project borrows critical tools from Feminist studies, Black studies and Postcolonial Caribbean studies to offer a framework for the aesthetic experience of VR immersion, figuratively and literally. I aim to foster conversations across disciplinary boundaries where those who work with the technology address it’s problematic histories, and thus make it more approachable as an area of research across the humanities, including for art historians, curators and artists.

How might perspectives from the Caribbean contribute to a process of decolonising technology?

This is a question I am addressing through my PhD. Building on my own experience as a white Euro-Jamaican, and past research in the portrayal of a hybrid identity within contemporary Jamaican culture, my artwork explores how this can be represented in VR. I’m also exploring the relation between hybridity and the representation of water through Kamau Brathwaite’s notion of “tidalectics”8 which sees water as a site of memory.

Decolonising VR technology through Caribbean perspectives is a multi-faceted project. Here are some of the questions I am grappling with right now, which I would love to discuss with more people from across the Caribbean and its diaspora:

- Why is the Caribbean a relevant place to think about relationships between the body and technology?

- While Caribbean thinkers have a unique and innovative understanding of modernity and exploitation through modern capitalist systems, how does a sometimes-limited access to the latest technologies affect a Caribbean analysis of local and global technocultures?

- From a Caribbean perspective, how does VR technology function as a ship: a virtual interface that allows us to move between different times and spaces in a non-linear way?

- From a Caribbean perspective, how does the experience of VR reimagine insularity – where participants interface the water virtually; where geographical dependency on the water and increasing environmental precarity are evoked through immersive images and sounds?

In closing, I return to your question Marsha – the one you posed back in 2015: “What might a Caribbean future look like?” I’m exploring this through VR and would love to have conversations with other people who find this relevant in their respective fields. Feel free to reach out if you find this interesting.

View Olivia McGilchrist’s work selected for the VRHAM! Virtual Reality and Arts Festival 2020 here

References:

- Carmen-Beatriz Llenin-Figueroa, “Imagined Islands: A Caribbean Tidalectics” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2012), 122.

- Kodwo Eshun, “Further Considerations of Afrofuturism.” CR: The New Centennial Review 3, No. 2 (2003): 287-302.

- Wayne Marshall, “Listening to the Sound of Culture.” Small Axe, Vol. 22, No. 1 (2018): 172-180.

- “Arthur Jafa, APEX_TNEG,” filmed February 2013 at MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. video, 01:50:08, accessed September 12, 2019, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TUBm2_v5RUw&t=5039s

- Nichole Lowe, “‘I’m not racist, but that’s funny’: Registers of Whiteness in the blog-o-sphere” (Master’s diss., University of Ottawa, 2012).

- Elizabeth M. DeLoughrey, “Heavy Waters: Waste and Atlantic Modernity.” PMLA 125.3 (2010): 703-712.

- Paul Gilroy, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1993).

- Kamau Brathwaite, ConVERSations with Nathaniel Mackey (Staten Island: We P, 1999).

Stay connected with Olivia McGilchrist:

Instagram: @oliviamcgilchrist

Website: oliviamcgilchrist.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.