A conversation between Marsha Pearce and Gwladys Gambie

Marsha Pearce: Gwladys it was lovely seeing you a few months ago, during the carnival season in Trinidad. It seems like aeons have passed since then. The pandemic has muddled time, days, months. How are you? How are things in Martinique?

Gwladys Gambie: Hi Marsha. It was also a pleasure for me to see you again. I am doing well – confined to my little apartment. Activities are slowly starting back in Martinique. We’ll come out of the lockdown on May 11th.

You’re participating in the 12th edition of the Mercosur Visual Arts Biennial led by head curator Andrea Giunta. The exhibition is themed “Feminine(s): Visualities, Actions and Affections” and it features work by female, non-binary and gender fluid artists. The event was scheduled to take place in Brazil, but the COVID-19 context now requires a virtual presentation. Please tell me about your work in the biennial, which has striking images of the black female body and Caribbean landscapes. What ideas and concerns are you addressing?

I had to create a series of India ink drawings and collages in situ, but the pandemic situation affected those plans. So, I am showing some sketches of what I planned to do there, and a few collages I did in Guadeloupe in 2018. I am also exhibiting some drawings I did during this lockdown.

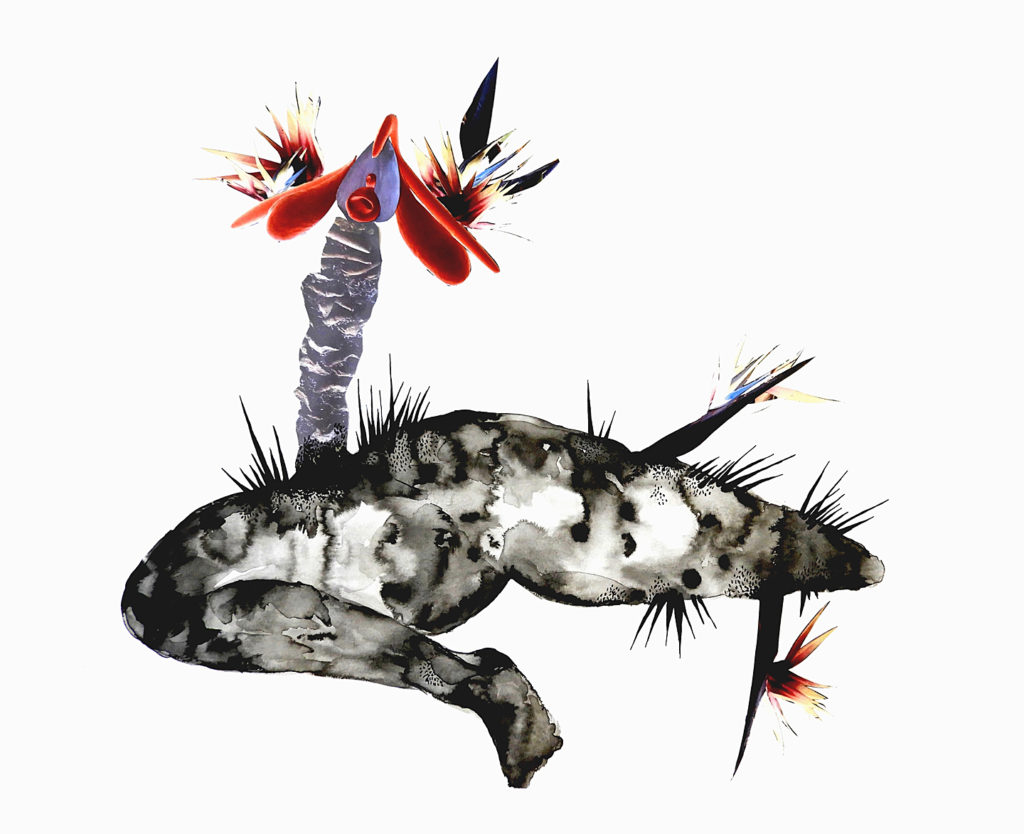

In the collage Poto Mitan (2018), I am addressing the issue of the female condition in the Caribbean space. Poto mitan is the central pillar in the Vodou temple. In the French West Indies, we use the expression as a metaphor to talk about women as the center of the family. Everything is organised around the mother. However, a lot of women reject this concept of Fanm Poto Mitan (Woman as Poto Mitan), because it restricts them – women feel it does not give them the freedom to be whatever they want to be.

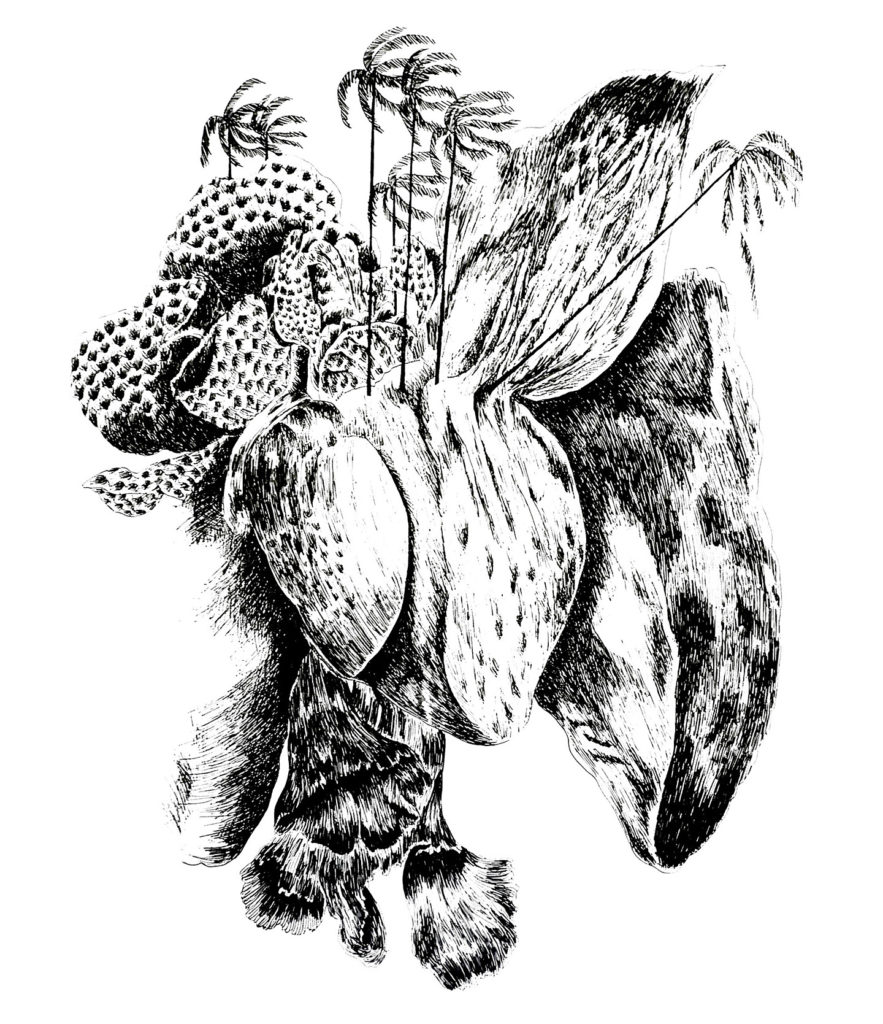

In my work, I consider ideas of sexuality, race and gender in a West Indian society, where stereotypes and the consequences of colonialism are still present. I am asking questions that relate to decolonial representations of the black female body – a decolonial feminism. In Anatomy of sensitive (2020), I associate human anatomy with flowers and organic shapes. I create little poetic eco-systems. I often combine the body and landscape because there are interconnections. We can see it in this surreal situation we are living in now. Our absence (our staying at home) is changing the earth. Nature can live without us, but we, fundamentally, need nature to live. I create, using the concept of “creole” to construct my own graphic/visual language.

The biennial’s theme “feminine(s)” makes room for a plurality or multiplicity of being. How does this theme resonate with you?

The feminine(s) theme resonates as a large field to be explored – one in which there is so much to do; to disassemble and remake. That exploratory work involves considering how to get out of the confines of social, aesthetic and sexual norms. The body, especially the female body, is a territory of oppression, of domination, of discrimination, of violence in a patriarchal society. How can we escape this condition? How can we break free of all these norms and injunctions imposed by society?

For black women, it’s about reconnecting with their Africanity, spirituality, ancestrality. It’s a physical and mental decolonisation. It is about re-appropriating themselves; finding their divinity, lost by years of domination and torture. It is about healing, step-by-step. We also can see this process with black men. Representations of men are changing . Hypermasculinity is not as systemic now. People are questioning toxic masculinity and talking about divine masculinity – whatever their sexuality.

You’ve created a personal myth in your work, involving the birth of Manman Chadwon or Sea Urchin Goddess. Tell me about this mythology. What is the significance of the sea urchin in your work?

Manman Chadwon is an Afro-Caribbean divinity, inspired by the water spirit Mami Wata, or Manman Dlo in Martinique. She is an avatar, or an alter ego for me. She represents power, the emancipation of black women – a decolonial representation of the body. She is the incarnation of freedom; of eroticism. This divinity protects woman; helps them to liberate themselves. Manman Chadwon represents the re-appropriation of the black female body, which has been denigrated and raped for a long time. Manman Chadwon brings me back to my African roots. I am interested in my Africanity. That’s why I am so fascinated by the powerful and mystical carnival character you have in Trinidad: the Moko Jumbie. I explored the Moko Jumbie character during my visit to Trinidad carnival this year and Manman Chadwon became Moko Chadwon.

I like to play with codes of femininity. Manman Chadwon has tree breasts with spines, and she wears monstrous high heels. Sometimes she has wings. It’s a strange femininity; not pleasant. She can be a hurricane. It’s about a big, powerful, black woman – sensual, savage. Her thorns are protection, defense, and pleasure.

The sea urchin is a wonderful creature. It looks like an explosion of sensations; of emotions. That’s why I choose to use the sea urchin in my work.

Myths or folklore are narratives that often play a key role in a society – as foundation or creation stories; as stories that carry the values and beliefs of a culture; as stories that respond to a particular time or context. Myths address questions about human existence. What mythological character do you imagine in this current pandemic?

I imagine Manman Toumo (Goddess Toumo). Toumo comes from Atoumo, a medicinal plant we use in Martinique. Atoumo sounds like: à tous maux in French, which means: “this plant can cure every ill.” Manman Toumo could be a divinity we call to protect our homes from disease, and to reinstate harmony and peace in hard times. She is inspired by Omolu, god of death and disease in Yoruba religion. People could put a few flowers from the Atoumo plant and honey to celebrate Toumo. Her colour representation would be white and pink.

Stay connected with Gwladys Gambie:

Instagram: @afrodite_glad

Website: gwladysgambie.blogspot.com

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.